Ornamental Gothics

Gothics History. Gothic typefaces are a broad group of styles rooted in medieval calligraphy and evolved into distinct print types during and after the invention of movable type via Gutenberg in the 15th century. They are sometimes confusingly named. In Europe “Gothic” usually refers to blackletter (medieval scripts), while in the U.S. “Gothic” often refers to sans-serif typefaces since the 1830s.

Gothic script is a broad term for the entire family of medieval European scripts that developed from Carolingian minuscule around the twelfth century. “Minuscules” are lower case letters as distinct from capital letters, or uncials. Type developed in the sixth through tenth centuries with modern lettering evolving from Carolingian scripts. The Emperor Charlemagne used these letters as an educational standard.

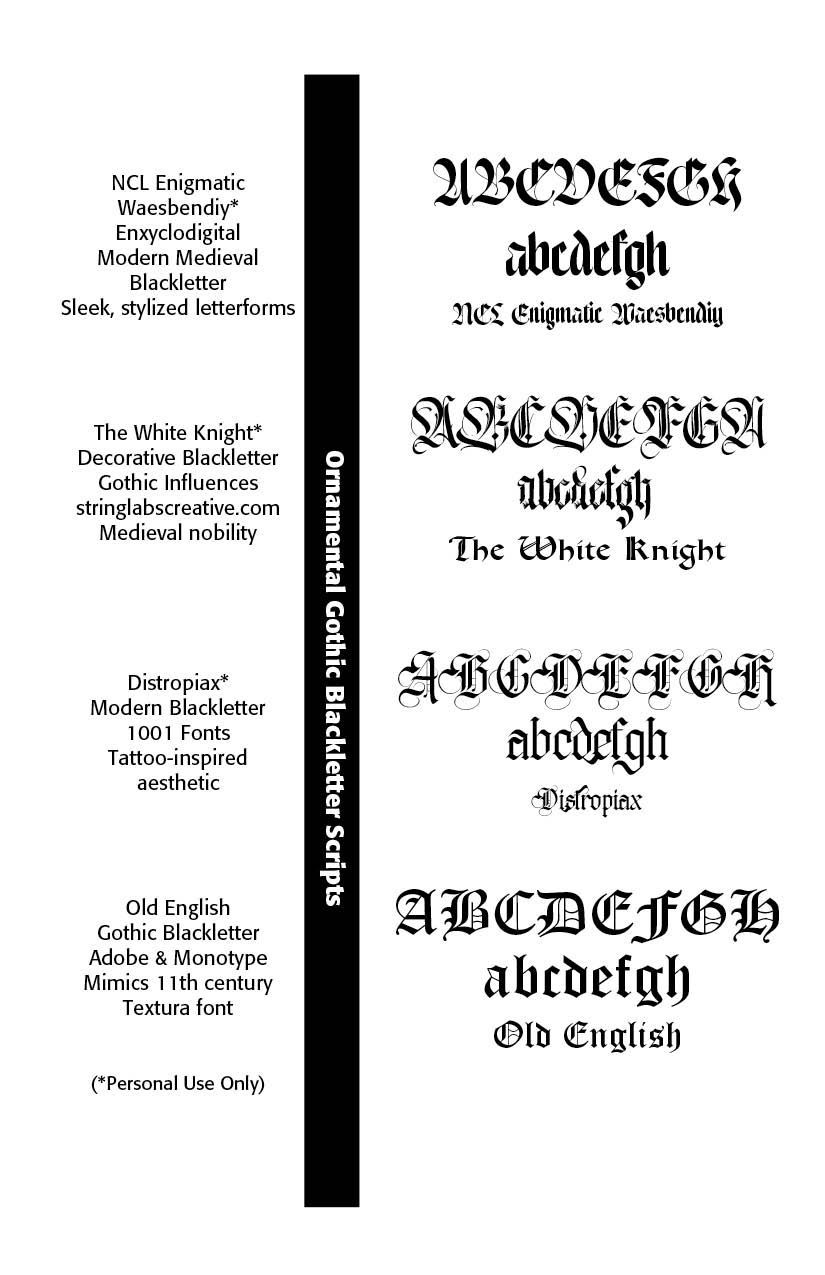

These densely packed scripts featured tall, narrow letterforms, strong vertical emphasis, sharp, angular connections, a dramatic thick/thin contrast and minimal spacing between letters. Gothic-inspired fonts create immediate medieval impact and work beautifully for titles, logos, and short display text. They are used today in Fantasy Gaming, Historical Projects, Themed Entertainment (like the Renaissance Fair), Book Design, Certificates, Breweries and Distilleries. Jack Nolan, a professional graphics designer, has provided a fetching display of such faces in his "33 Medieval Fonts Perfect for ‘Ye Olde’ Designs in 2025."(1)

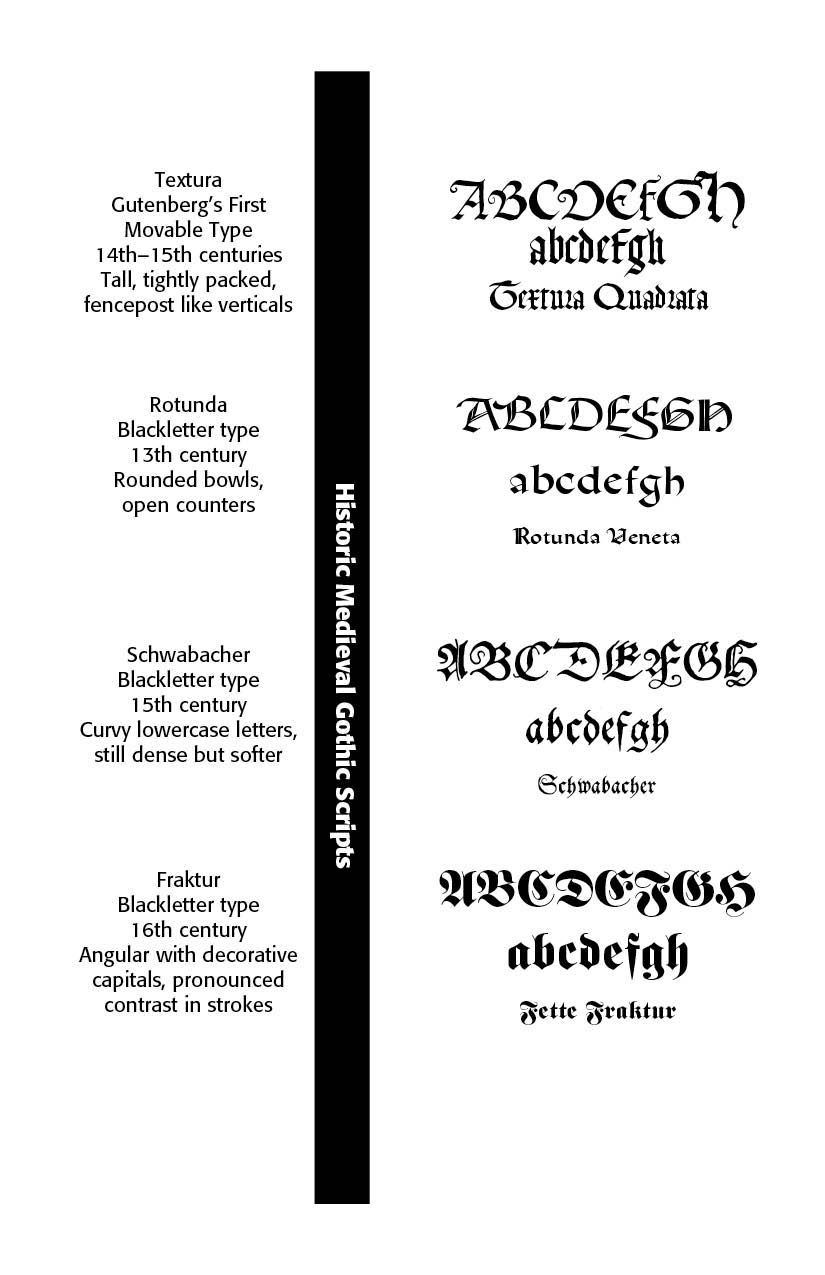

Substyles

Substyles of Gothic script developed in several major typefaces — Textura, Rotunda, Schwabacher, and Fraktur. Textura (Textualis) has very dense, upright, tall little-spaced letters with sharp, angular strokes and minimal curves. The vertical emphasis offers almost no slant and there are diamond-shaped serifs at stroke ends.

Textura was used in the Gutenberg Bible along with other formal and liturgical documents. Old English Text has heavily borrowed from Textura Quadrata. (I have traced some of this history in two books I wrote — Bible Typography: A History of Bible Printing and Versions, and Typographical Beauty Through the Ages: A Christian Perspective, both available from Lulu Press [lulu.com]or on Amazon.)

Rotunda, with its rounded bowls and more open counters, is rounder and more open than Textura, thus, easier to read. It has softer curves and fewer broken strokes, more spacing between letters and blends elements of Carolingian minuscule with Gothic verticality. Rotunda was mostly used in southern Europe and Italy.

Schwabacher was a transitional form between Textura and Fraktur, with moderate curves. It has round lowercase letters, more flowing that Textura but denser than Rotunda. Distinctive shapes are “g” and “s.” This face was popular in German books in the late fifteenth – sixteenth centuries.

Fraktur, the most famous German blackletter type, was widely used from the 16th to early 20th century. It has broken yet ornate strokes with both sharp and curved elements. Tall ascenders and elaborate capitals made it the official German type in publications and newspapers until World War II. Its Nazi associations and use with German nationalism due to its use in Nazi propaganda makes it suspect in politically sensitive contexts.

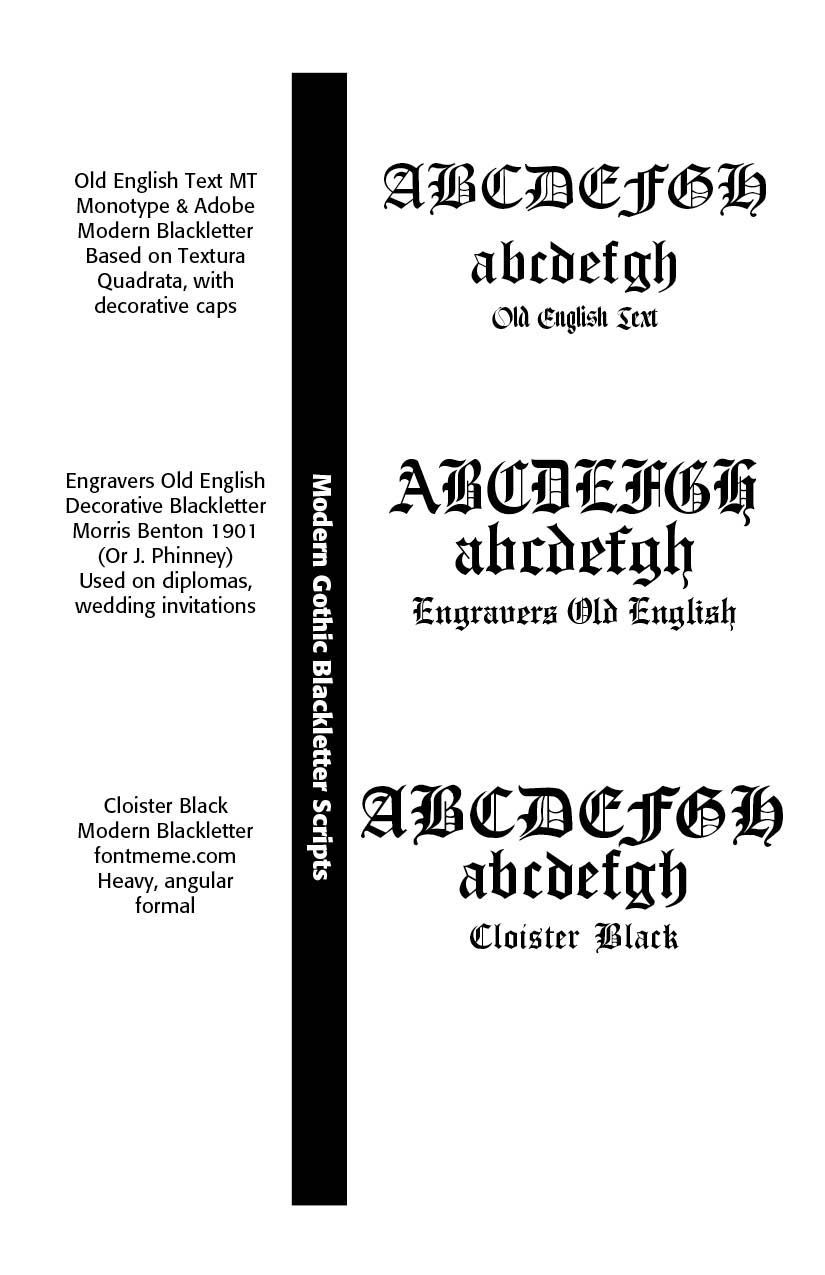

Modern revivals have seen these historic Gothic faces used in diplomas, certificates, beer labels, metal bands, and logos. Old English Text (see Below), Engravers Old English and Cloister Black are favorite faces. These Gothics were gradually replaced by Roman typefaces for readability. Nazi Germany’s later ban on Fraktur in 1941 ended its official use.

Gothics & Old English Typefaces. There is often confusion between Gothic Blackletter faces and what we call Old English type. What we can say is that All “Old English” fonts are Gothic, but not all Gothic fonts are “Old English.” The true Old English language was never written in what we call “Old English font” today—that name is a modern typographic misnomer.

The term “Old English” in typography usually refers to blackletter styles, particularly Textura Quadrata. However, this is somewhat misleading as the actual Old English language (Anglo-Saxon, used from the fifth through eleventh centuries) was typically written in Insular scripts, which look quite different from the later blackletter styles many associate with “Old English” typography. “Old English” was actually the language of the Anglo-Saxons until the mid 1100s and they had nothing to do with Blackletter. Centuries after Blackletter’s initial emergence, “Old English Text” was the name of a font by Monotype that mimicked eleventh century Textura.

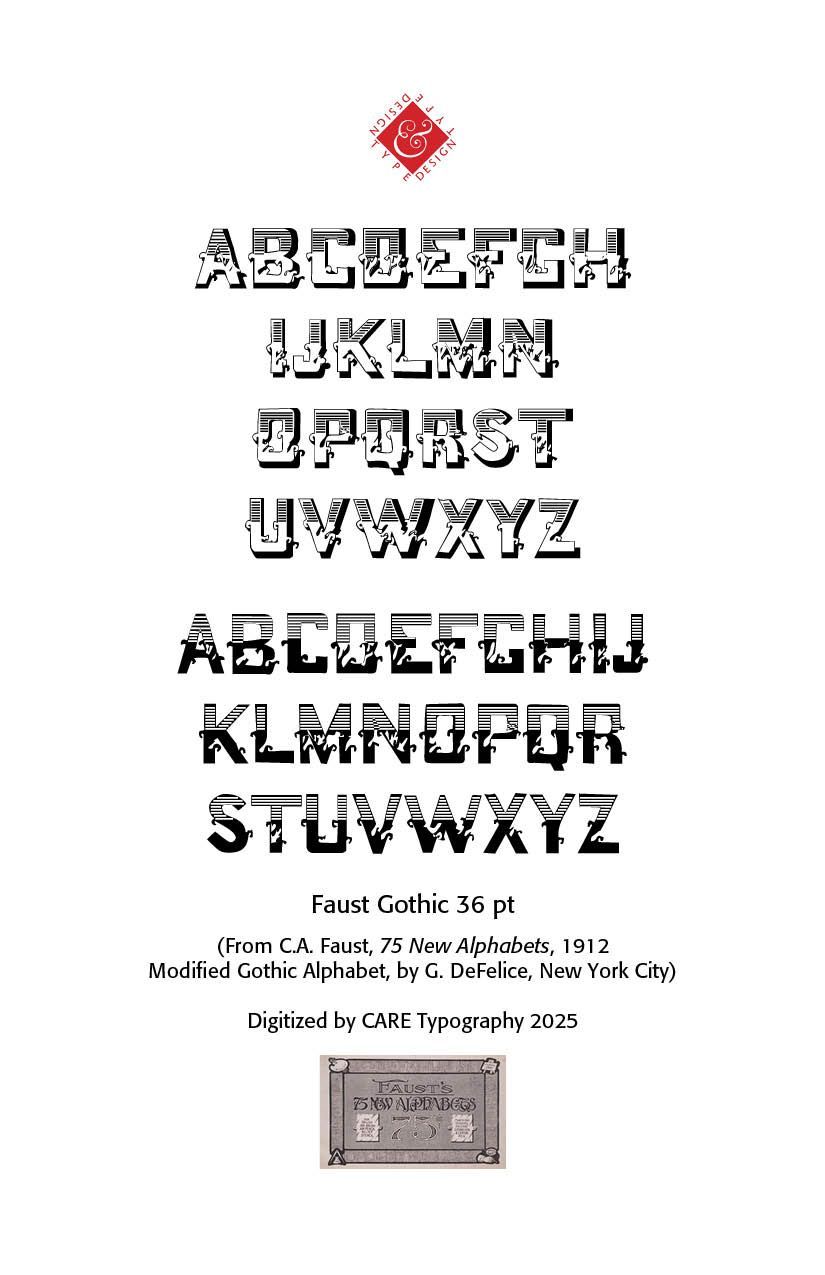

Modern Old English fonts include Old English Text MT, which is based on Textura Quadrata, often with decorative capitals, Cloister Black, Engravers Old English, used on diplomas and wedding invitations, and a number of Ornamental variations with type foundries sometimes adding swashes, outline versions, or engraved shading to classic blackletter faces, such as those in the Faust Gothic typeface.

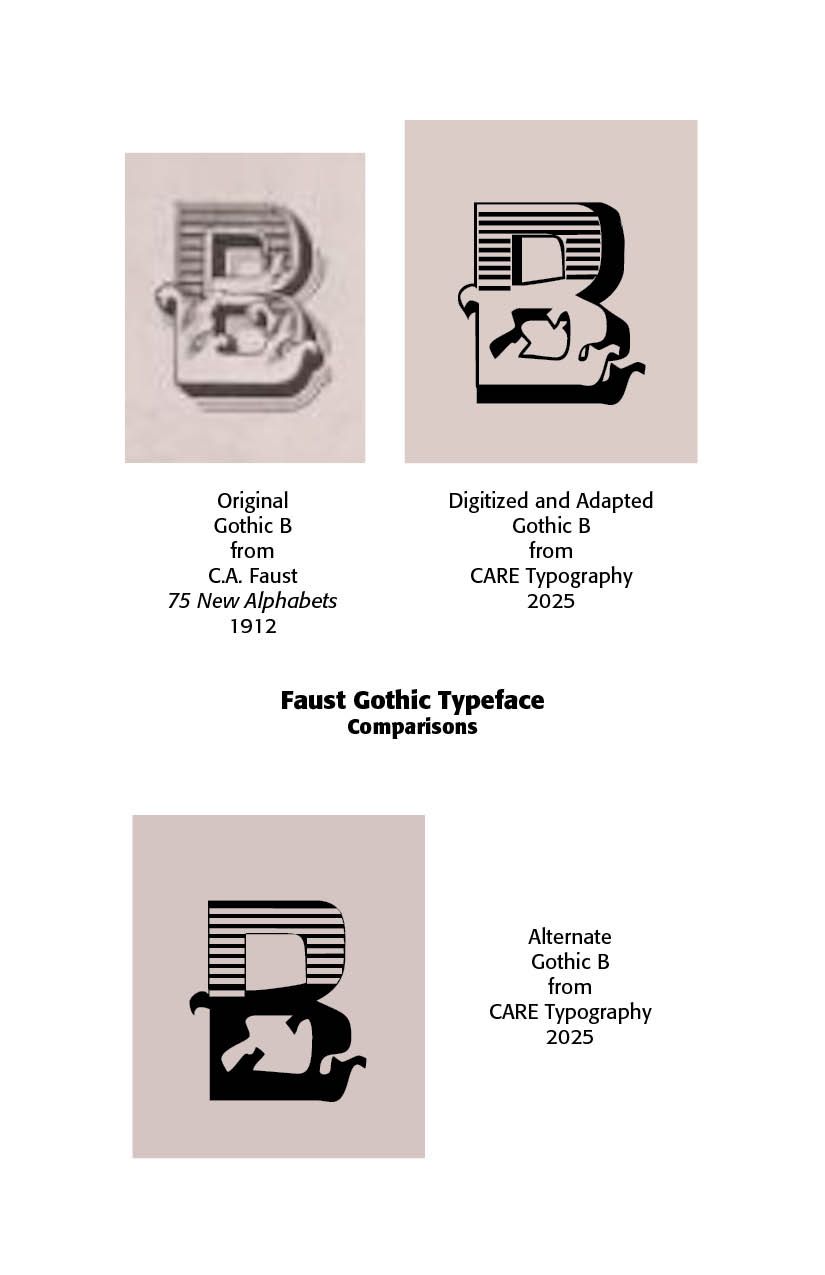

Ornamental Gothic Fonts. Ornamental Gothic fonts possess elaborate capitals, initial letters that are often highly decorated, with swirls, flourishes, or foliage (sometimes called “Lombardic capitals” when round). These capitals may contain internal ornamentation such as hatching, shading, or miniature drawings. A fine example is the font found in C.A. Faust’s 75 New Alphabets in showcasing a Modified Gothic Alphabet, by G. DeFelice, New York City. This font has been digitally recreated and adapted for use by CARE Typography. It is available for purchase and use.

Such ornamental fonts have intricate strokes, with stems and crossbars that may include spur-like extensions, curls, or diamond finials. Pen strokes often show “broken” or “fractured” angles that create a textured look. Thick verticals and thin connecting lines give a dramatic texture. Many ornamental Gothic faces accentuate this contrast with embellished serifs or small spikes. Some of these fonts have decorative ligatures, letters are frequently joined in ornate ligatures (e.g., “ct,” “st,” “Th”). These ligatures may have extra curves or swoops that fill the space between letters.

Ornamental caps may use color and gold in original manuscripts. Historically, ornamental Gothic scripts in illuminated manuscripts often included red, blue, or gold initials, with pen-drawn filigree or “trailing vines” (called flourishing or “rinceaux”).

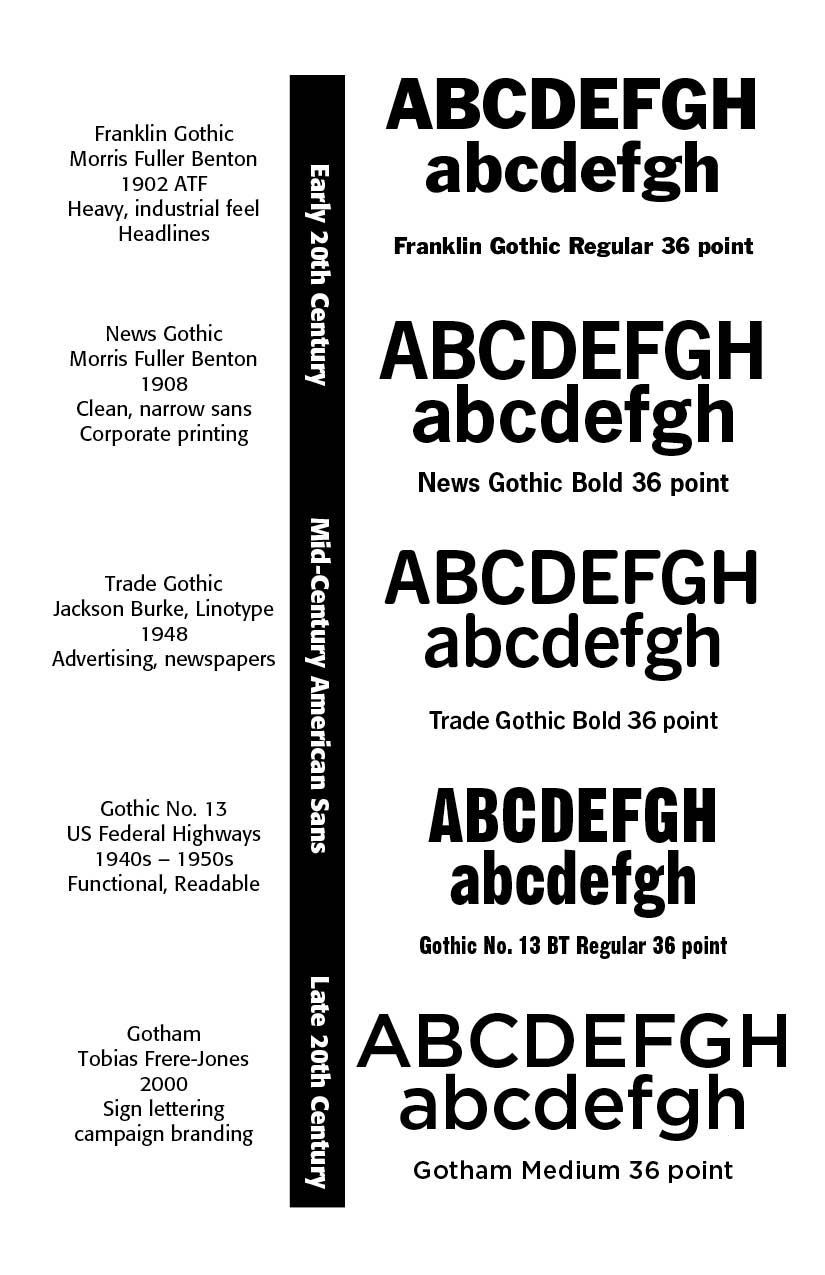

Modern American Gothics. “Gothic typefaces” in American usage historically refer not to medieval blackletter scripts (as in Europe), but to sans-serif typefaces, especially from the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth century. American printers and foundries used the term “Gothic” for what we’d now simply call sans-serifs.

As early as the 1830s, “Gothic” became the standard name for sans-serif display faces. They were mostly used for advertising, posters, and signage rather than book typography. Key features included condensed proportions, simple strokes, minimal contrast, and sometimes quirky letterforms. Boston Gothic (c. 1837) was one of the earliest American sans-serifs. Franklin Gothic (1902, Morris Fuller Benton, ATF) with its heavy, industrial feel, became a dominant American sans-serif for headlines. News Gothic (1908, Benton, ATF) was lighter and more neutral than Franklin Gothic, ideal for newspaper text and display.

Trade Gothic (1948, Jackson Burke, Linotype) is a workhorse sans used heavily in advertising and newspaper headlines. It is more irregular and “lively” than the geometric European faces (like Futura). Gothic No. 13 / Highway Gothic (FHWA Series, 1940s–50s) was designed by the U.S. Federal Highway Administration for road signage. It is functional and legible at distance and speed rather than stylish.

Gotham, an example of late twentieth century Neo-Gothics (2000, Hoefler & Frere-Jones), is based on mid-20th century American sign lettering and architectural sans-serifs. It gained fame in Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign branding. Gotham’s designer notes that “Gotham celebrates the attractive and unassuming lettering of the city. New York is teeming with such letters, handmade sans serifs that share a common underlying structure, an engineer’s idea of “basic lettering” that transcends both the characteristics of their materials and the mannerisms of their makers. These are the cast bronze numbers that give office doorways their authority, and the markings on cornerstones whose neutral and equable style defies the passage of time. They’re the matter-of-fact neon signs that emblazon liquor stores and pharmacies, and the names of proprietors plainly painted on delivery trucks. These letters are straightforward and non-negotiable, yet possessed of great personality, and often expertly made. And although designers have lived with them for more than half a century, they remarkably went unrevived until 2000, when we introduced Gotham.”

SOURCES

(1). 33 Medieval Fonts Perfect for ‘Ye Olde’ Designs in 2025

Jack Nolan Updated Jul 23, 2025

https://designworklife.com/medieval-fonts-fantasy-or-renaissance-flair/

He highlights Silvermoon, Goldiwak, The Quironax, Synthetic Stone, Dragonhelm, Inkwell Scribe, Dragonit, Cikond, Hortens, Black Kinger, Black Baron Typeface, NCL Jurgen Farbache, Basefigh, Raven Hell Round, Iron Steel, Odd Times, Enigmatic Waesbendly (Modern Blackletter), Falcone, Enchant, Marcus, Windshire, Fenrir Gothic, Ambrosia, Heraldic Shadows, The Hero King Typeface, Raven Hell Regular, Wicked Knight, Lordish Blackletter, The White Knight (my second choice), Distropiax (3rd choice), King Castle, Moleta, Othelie.

Successful Layout & Design