Mac Mini M1 OR Studio?

Through the modern years, Mac Mini's have kept their shape and design — with a width and depth of 7.7 inches and 1.4 inch height. The newest Mini M1 weighs 2.6 pounds and fits nicely beside my desktop monitor.

The new Mac Studio has either the M1 Max chip or the M1 Ultra chip driving the computing power. The M1 Max chip is a 10-core CPU with 8 performance cores and 2 efficiency cores, with a 24-core GPU and 16-core Neural engine. The M1 Ultra chip has a 20-core CPU, a 48-core GPU and a 32-core Neural engine. What all of this means is that this beast is FAST — especially at video rendering and production.

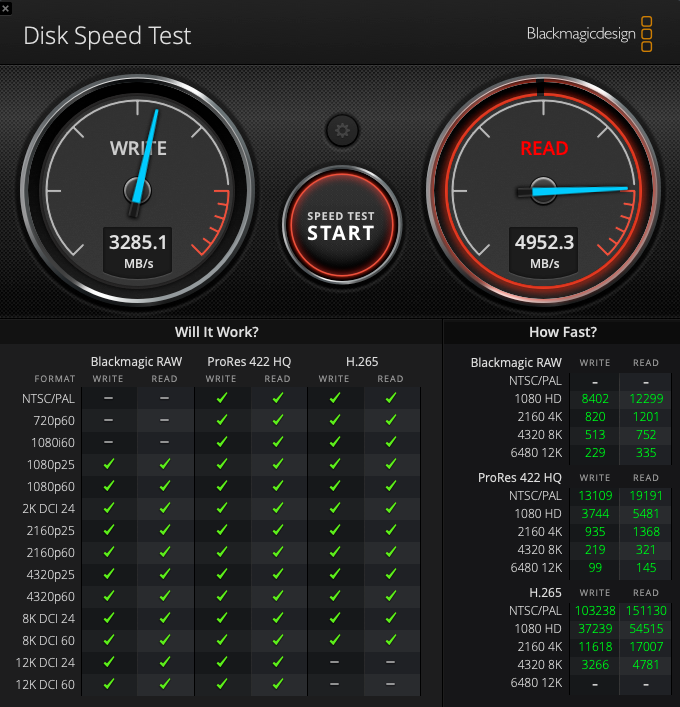

Mac Studio typical speed test.

With the Apple release of the new Mac Studio in 2022, users who have relied on Mac Mini's on their desktop are left with the question of which one to use for them. Both machines use the newer M1 chip in their architecture, giving a notable speed boost to everything from ordinary computer use to layout and design with Adobe products. I have used numerous Mac Mini's through the years, from the humble 2005 PowerPC model through the Intel models in the mid-2000s all the way to the latest Mac mini M1 released in 2020.

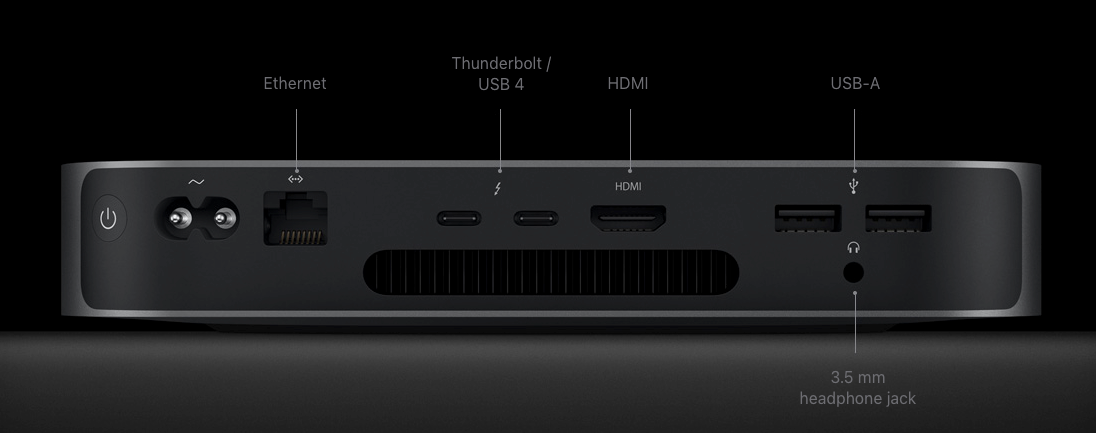

The back of the Mini M1 has two Thunderbolt/USB 4 ports. with two USB-A ports, a HDMI port and a Gigabit Ethernet port (configurable to 10Gb Ethernet). A 3.5 mm headphone jack is included. Of course, Wi-Fi and Bluetooth are built in, along with a built-in speaker. This Mac can support up to two displays, one with up to 6K resolution and another with up to 4K resolution. This is a powerful machine for its size and stature!

Although it's height is bigger than a Mini (3.7 inches), it is still 7.7 inches by 7.7 inches in width and depth. The biggest seen difference here is in the multitude of ports on the back and front of the Studio. There are four Thunderbolt 4 ports (up to 40 Gb/s), a Display port, two USB-A ports (or USB 4 and USB 3.1) a HDMI port, a 10 Gb Ethernet port and a 3.5 headphone jack port. The front of the M1 Max Studio has two USB-C ports and a SDXC card slot. What the Mini M1 lacks in ports, often needing external help in getting extra ports, the Mac Studio has them all built-in.

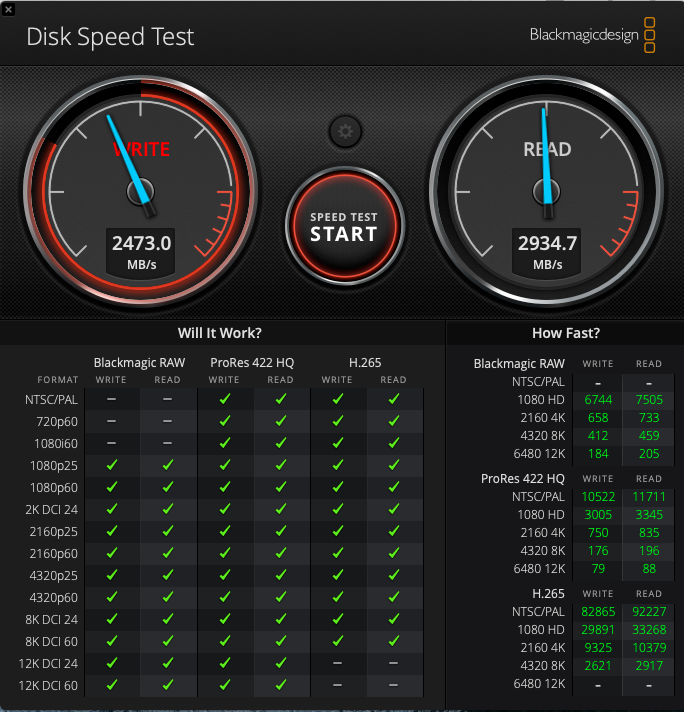

Mac Mini M1 typical speed test.

The Mac Studio outpaces the Mac Mini M1, as it should. Of course, others have done more extensive speed tests (find them on YouTube). The speed differential in normal computer work is not that great.

The Mac Mini M1 is a lot cheaper ($699 to $899 retail) than the Mac Studio ($1,999 to $3,999 retail) and its power is quite adequate for most normal computer tasks. The Mac Studio is a pro-sumer computer, less than a professional Mac Pro computer ($5,999 to $6,499 retail), an in-between computer for those wanting multiple displays and faster video editing capabilities or a multitude of high memory use programs simultaneously open. The 8 Gb or even 16 Gb memory option for the Mac Mini pushes the limits of memory use for memory-hogging programs. Notably, a super fitted Mac Mini computer costs about the same as a base line Mac Studio.

Which of these two smaller fitting desktop computers should you buy? It all depends on your use of them and the programming you use on them. I like the faster Mac Studio with its built-in 32 – 64 Gb memory options contrasted to the 8 – 16 Gb memory options on the Mini M1. I also like the multiple ports on the Mac Studio, if you can afford it.

Successful Layout & Design