AI & Typography: A Christian-Theistic Look

AI & Typography: A Christian-Theistic Present Look

Monotype Corporation recently released their 2025 Report concerning Artificial Intelligence and Typography called Re-Vision (See https://bit.ly/4aEUePf). This eReport looks at the various typographical, social and cultural issues surrounding AI and how it affects and impacts the craft and science of typography. A selected summary of the Report is available below.

What I want to do in this brief post is to address three questions that were raised in this Monotype report — What is it that we do that a machine will never be able to do? What is an essentially “human” typographic experience? Can AI be fully commanded, and interrogated, or will technology sanitize our vision and overthrow our own artistic hands?

While AI holds forth some fascinating and interesting scenarios for the future of typography, my own deep dive into the technology, as a pastor/theologian/ typographer has given me both an appreciation for the technology and suitable warnings for our humanity. A couple of seminars I conducted on AI have helped me frame the discussion with God-given “human” insights. The human concerns keep surfacing here — Will AI replace us in some significant way? Will AI even surpass us in its ability to accomplish things that we always thought were unique to human efforts? Will AI eliminate the Picasso’s? Or the Gutenberg’s? Or the Garamond’s? Or the Baskerville’s? Or the many other typographical giants through the centuries? Will AI robotics replace our relationships? How will AI integrate with our typographical and cultural journeys?

The specter of a post-human world where we have an informational pattern over material existence, and our bodies are an accident of history and unnecessary, where consciousness is merely a secondary result of our evolution, where the body is merely a prosthesis, an artificial part, where human beings can be wedded with intelligent machines, and finally where we are merely a “sum of our parts,” no longer needing divine intervention, guidance or creativity, looms before us in AI.

Christopher S. Penn, Almost Timely News, noted on August 3 of this year that “AI is advancing so rapidly that if your preferred tool or ecosystem doesn’t have a useful feature today that another platform does, there’s a very good chance in 3-6 months that your tool/ecosystem will. Overall, AI’s capabilities, in terms of the complexity of tasks it can handle, doubles roughly every 6 months. A task AI couldn’t do a year ago, it can probably do in some capacity today if the model’s architecture permits it.”

“The true menace of AI is not so much what it’s capable of doing today, but rather that it doesn’t rest. An AI program can learn, evolve, iterate, and work 24/7. Give it a job and it will toil sleeplessly until the task is complete. That’s a wonderful advantage if the job is, say, parsing cancer research data, but less so if it’s practicing and refining a creative craft that threatens to eventually put thousands of people out of work.” (Re-Vision Report, Monotype, Winter 2025)

As a Christian typographer and thinker, I am reminded of the biblical story of the tower of Babel in Genesis 11 — “This is autonomous self-aggrandizement and bringing God down to us rather than us worshipping him. Babel stood—and still stands today—as a type of the earthly city, in rebellion against God. . . . They name their city Bab-el, Akkadian for “gate of the gods,” but God makes their ambition a byword for babel: a near homonym for the Hebrew word meaning “confusion.” God gives Babel or Babylon a different destiny and meaning and forces his sovereign will on mankind.” (Christopher Watkin, Biblical Critical Theory)

To be made in God’s image means we are not just able to process and display, but we are called to create and express ourselves. This is a wonderful, glorious thing. But when we use that creativity to fashion something to think, speak, and create for us, we start to abdicate our role as Imago Dei and in a sense become less human. By delegating our God-given task to coding, we deny who we are and who God is.

The technology manager of the Seminary I attended noted this — “When the massive flood of AI-generated content drowns out both the well-crafted painting shared on Instagram and the random shower-thought posted to X, we might finally understand that the punishment for the idol maker is true. Our voices will be buried under the rising volume of AI-content, our vision will be blinded by the warping and blending of reality, and our hearing will be deafened by the noise of AI voices speaking AI-generated opinions.” ( Paul Quiram, Mgr. Ed Tech, Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia, PA)

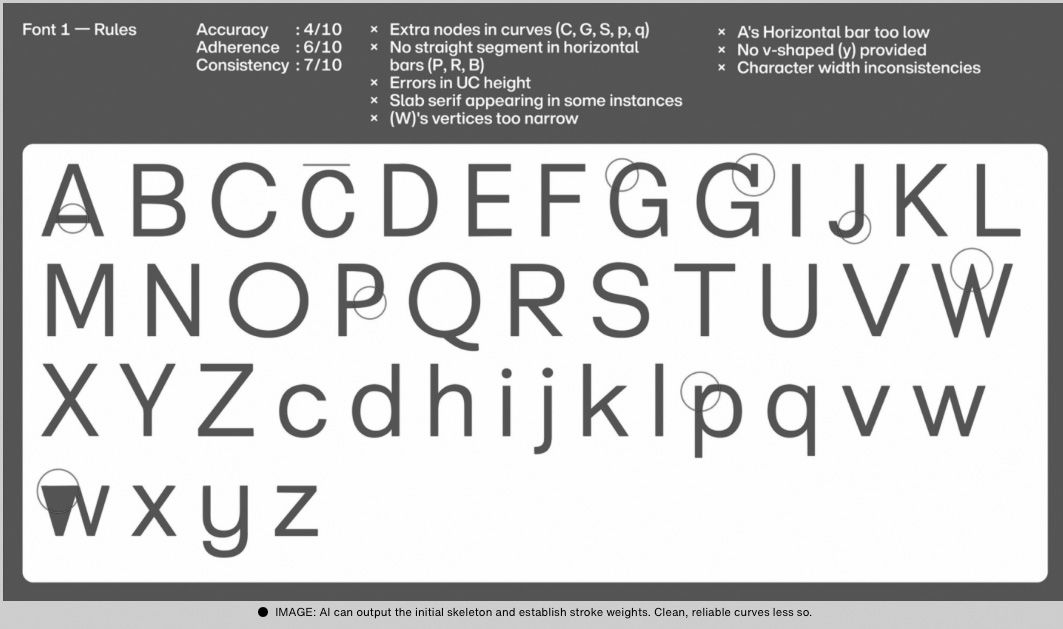

Campbell goes on to say that “To recreate the work that designers have been doing since the days of illuminated manuscripts and the Gutenberg Bible is no simple feat,” Campbell rightly points out. “At this stage in the evolution of AI tools, the models built on statistical probabilities struggle to recreate the simple beauty of well-designed, meticulously crafted typography.”

What is it that we do that a machine will never be able to do?

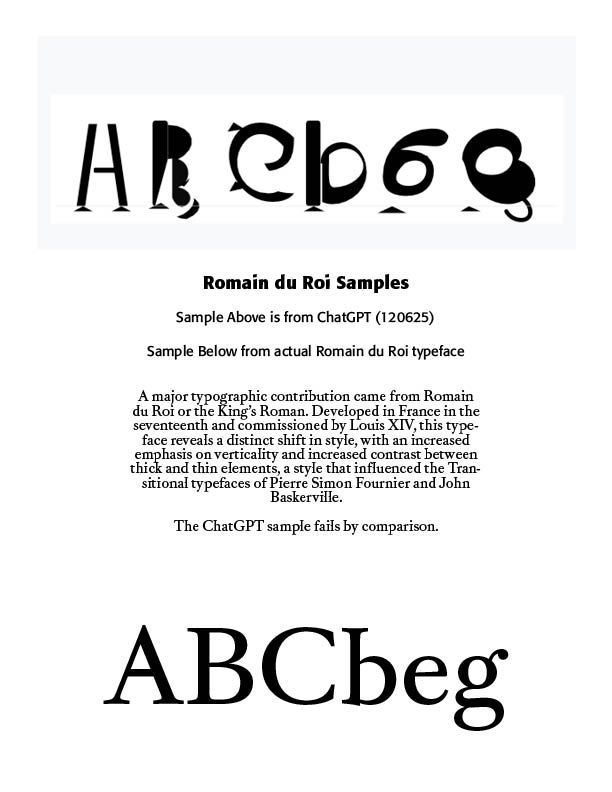

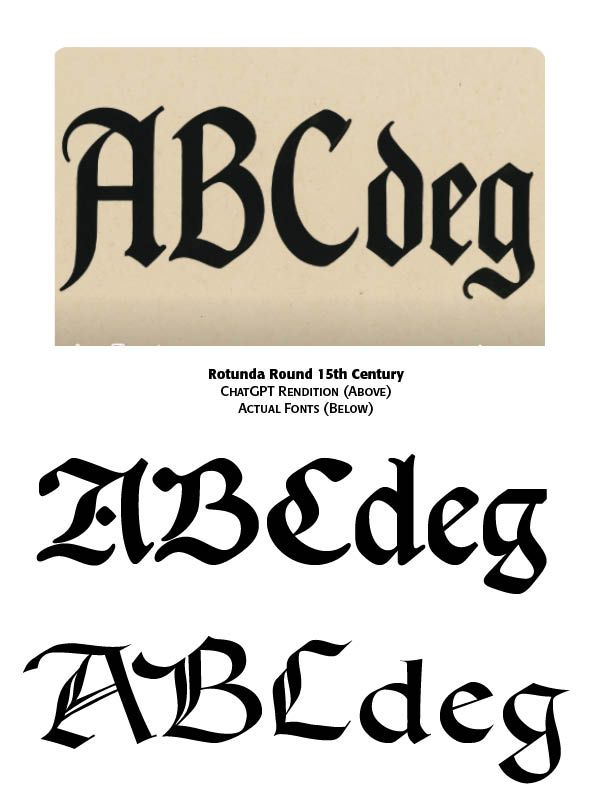

What Monotype found out in their reporting about AI now is that the technology is clearly lacking in typographical preciseness and artistic coherence. “But for better or for worse, it turns out that AI is fairly bad at drawing letters. In a recent piece in The Atlantic (a piece that, it should be noted, was sponsored by Google), writer Drew Campbell observed that while AI knows many words and may already know all the words there are to know, it “stumbles” when “creating the literal letterforms that construct each syllable, clause, and paragraph.” (Monotype and see “Typography Reconsidered,” Drew Campbell, The Atlantic at https://www.theatlantic.com/sponsored/google/typography-reconsidered/3886/)

In my own experimentation with AI tools in typographic design, I asked ChatGPT to give me a typeface in Rotunda rounded Gothic type of the 15th century in the letters, ABCdeg. This is what it came up with. Looks “like” rounded Gothic, but not really. I also asked AI to give me those letters with the typeface of Romaine du Roi, a very carefully crafted typeface of the Enlightenment Period in the 1700s. It came up with these letters, a terrible rendering.

Of course, this does not mean that AI cannot ever duplicate these typographical periods and faces. But it does point to the need for “human” based typographical input and guidance and critique. Monotype’s conclusion — “Whether the work is done by our team or others in the industry, we believe human beings should remain central to typographic ideation.”

Christopher Penn offers four ethical tests or guards to be applied to AI which can easily apply to typographical standards and creations —"Respect — Does our use of AI respect the values we've established? Harm people? Devalue people? Accountability — Who is responsible for AI outputs? Does the AI dodge liability? Fairness — What known biases does any given AI model have? Transparency — The more transparency, interpretability, and explainability there is in any AI system, the safer it is. The more trustworthy it is.” (Almost Timely News: The Ethics of AI by Christopher Penn, August 17, 2025)

“AI should not be feared, but designers are yet to form a consensus. What feels pertinent is that we as design “humans” define the value we bring to our role in ideation and execution. If nothing else, AI has prompted introspection on creative methodologies, a reappraisal of our relationship to technology.” (Monotype Report)

From a Christian ethical point of view, “We must engage these issues, rather than respond after their effects are widely felt. But we don’t have to face today or tomorrow with fear. God is sovereign and his Word is sufficient for every good work, so we are able to walk with confidence as we apply his Word to these challenges with wisdom and guided by his Spirit.” (Jason Thacker, The Age of AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Humanity, Zondervan, 2020)

Successful Layout & Design