Early German Typography (Part 2)

Herbert Hoffmann, Albert Bruckner, Max Hertwig, and Rudolf Koch collaborated on a typographic “atlas” or specimen book titled Hoffmanns Schriftatlas: Das Schriftschaffen der Gegenwart in Alphabeten und Anwendungen (1930) (Hoffmann’s Type Atlas: Contemporary Type Creation in Alphabets and Applications) Also distributed in France under the title Alphabets by Herbert Hoffman and other collaborators by Arts et Métiers Graphiques magazine, it is a specimen of alphabets, initials, monograms, logos and other typographic forms from early German typography. The atlas captures typographic modernism in Germany around that time, including influences of the Bauhaus and the modernist movement. It is considered a rich visual record of type and lettering design in that period, showing both experimental and traditional forms.

In Part One of this series, we investigated the typography of early Germany through the lens of Rudolf Koch, Louis Oppenheim, E.R. Weiss, Lucian Bernhard, Friedrich Wilhelm Kleukens, and Bernard Naudin. In this Part Two we revisit the typography of Ernst Deutsch, Friedrich Heinrichsen, Benjamin Krebs Nachfolger, Maria Ballé, Margarete Leins, Anna Simons and take a brief visit to the Ecole des Arts et Metiers in Stuttgart.

Ernst Deutsch (1887–1938). Born in Vienna, Austria, Ernst Deutsch first worked as a costume designer and studied under Gustav Klimt. In Paris, he worked he worked on costumes for Coco Chanel, before moving to the United States in 1929, where he changed his name to Ernst Dryden and was employed from 1933 onwards as a costume designer for Universal, Columbia and Selznick in Hollywood. He died in Los Angeles in 1938

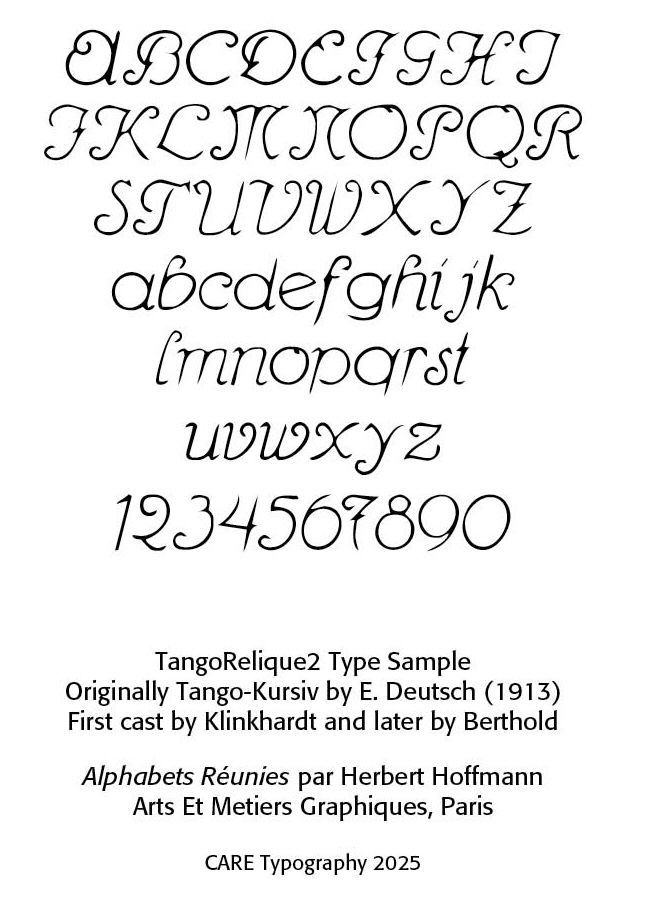

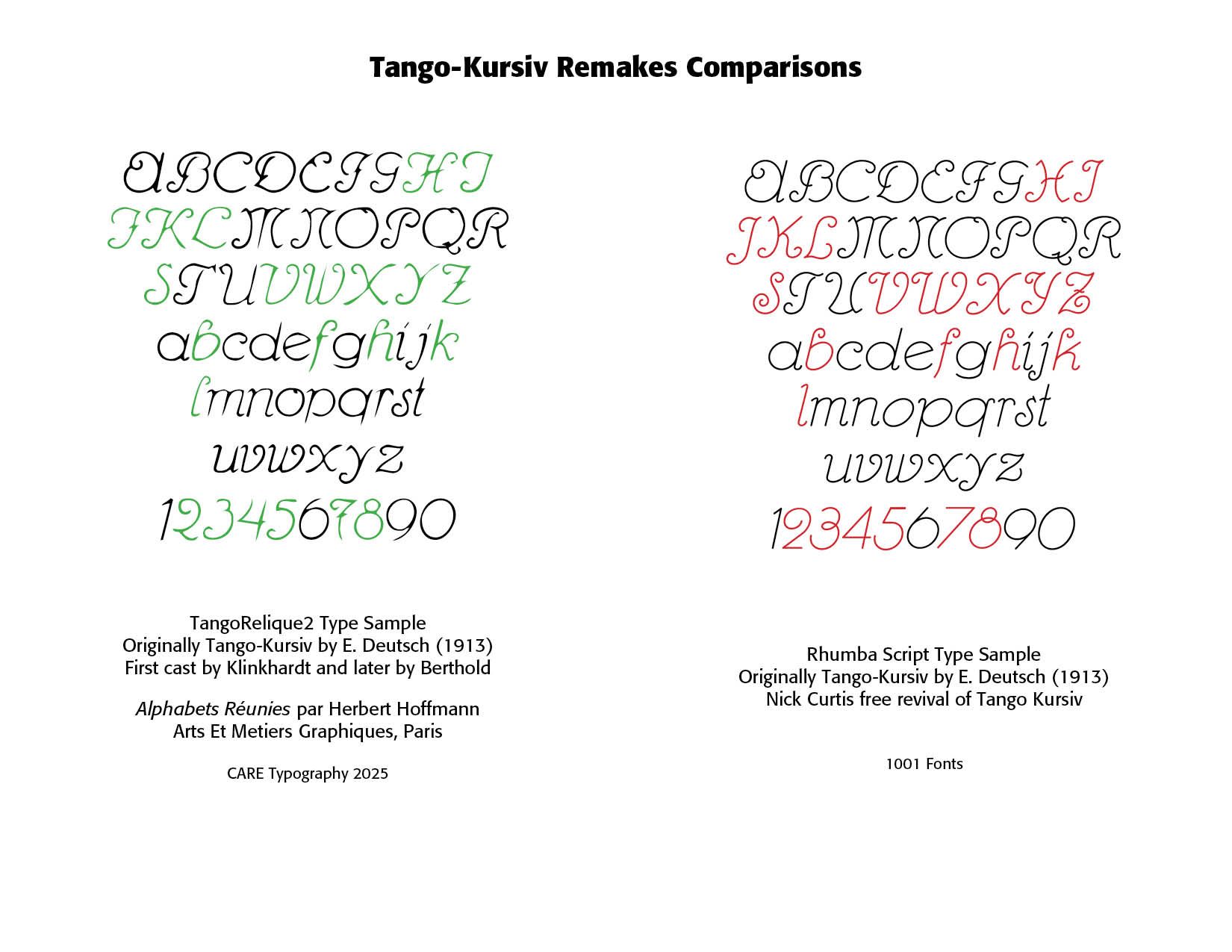

In typography, Deutsch designed Tango Kursiv (1913), Tango Antiqua and Tango Antiqua Halbfelt (1916). He was known for designing display lettering and poster typography, especially in the pre-World War One period. Digital revivals have been offered by Nick Curtis in his Rhumba Script NF, a free revival of Tango Kursiv, and Oliver Weiss in his WF Paletti in 2016–2017. Deutsch fonts have strong display orientation, with elegant, somewhat decorative, but still relatively clean visual style. We also see the influence of early twentieth-century graphic design movements in Europe in the Art Nouveau/Jugenstil, poster arts, and his exposure to Paris-based design sensibilities

This is a photograph of the typecase for Tango-Antiqua. It was captured by Albert-Jan Pool in Wetzig's Handbuch Der Schriftarten from 1926 in visiting Katharina Jesdinsky's print workshop in Kiel in 2017.

Friedrich Heinrichsen (1901–1980). Heinrichsen worked as a typographer and graphic artist. Part of his training came under Rudolf Koch, becoming his assistant in Offenbach in 1924. After World War Two he taught typography, was involved in rebuilding efforts and worked on industrial, advertising and church commissions.

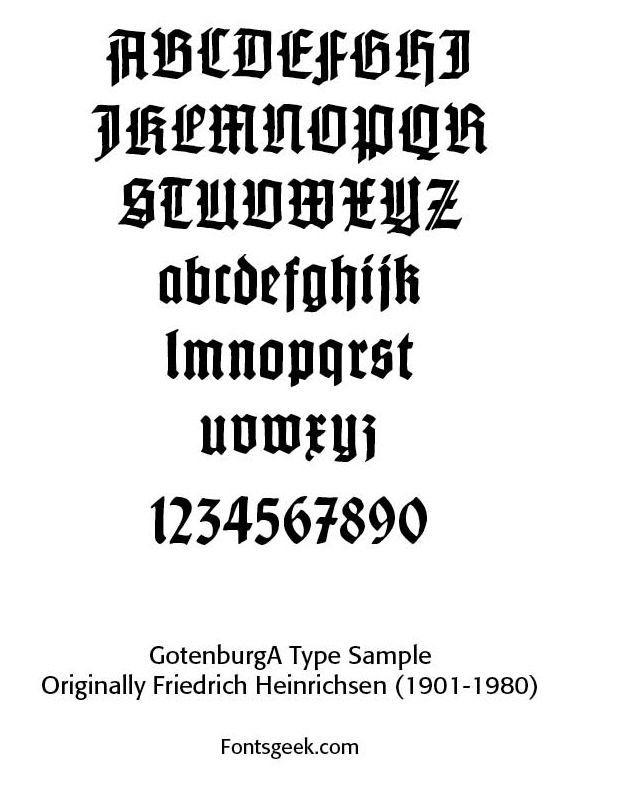

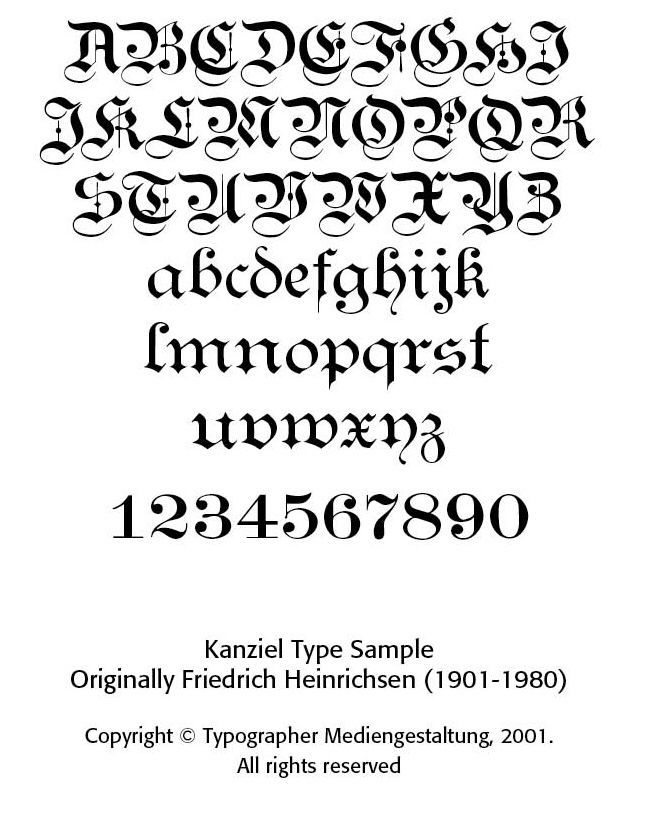

His best known typeface is Gotenburg. Gotenburg is a “broken grotesque” style font, referencing old blackletter or fractured styles and sans/grotesque styles for letter forms. Gotenburg comes in Gotenburg Bold and decorative variants in Gotenburg A and B. He also designed the Heinrichsen-Kanzlei face. As part of the Offenbach School, he emphasized craftsmanship, calligraphic roots and the integration of letter-forms with ornamentation and strong design sensibilities.

Benjamin Krebs Nachfolger (or just Krebs Nachf) founded one of the significant German foundries in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It produced many typeface designs, especially what is referred to as blackletter (“Fraktur”) and early sans-serif (Grotesks) as well as display and decorative type. Blackletter faces included Normale Fraktur, Neue Fraktur, Kunstler Gottisch, Psalter Gottisch and Kaiser Gottisch. A history of Krebs Nachf was written by Gustav Mori in 1916. The firm was taken over by Ludwig & Mayer, and then Klingspor and finally by Stempel in 1933.

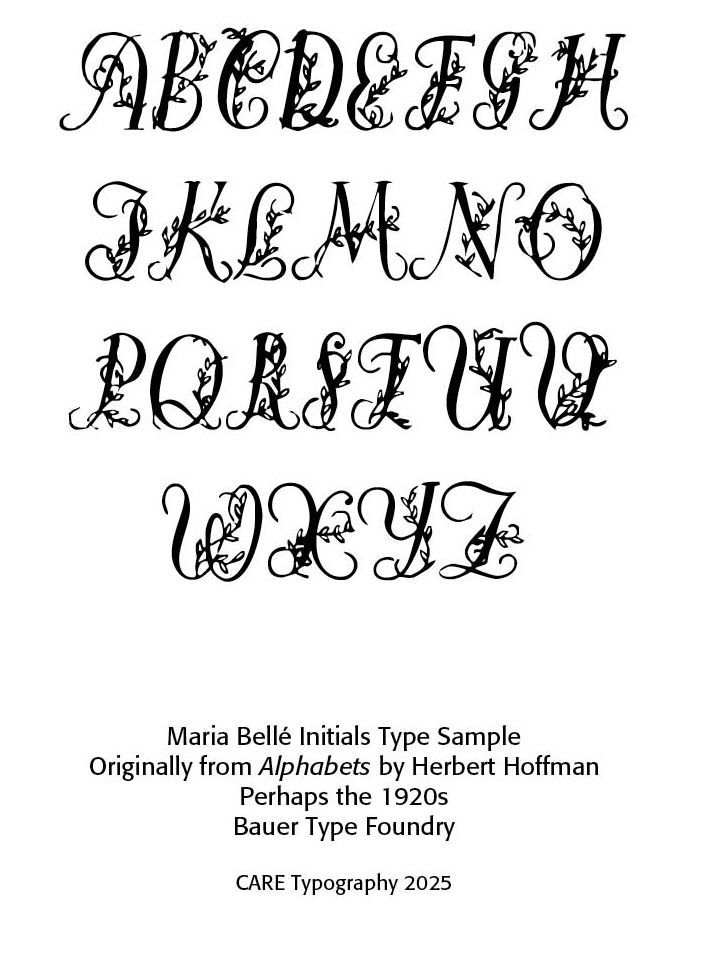

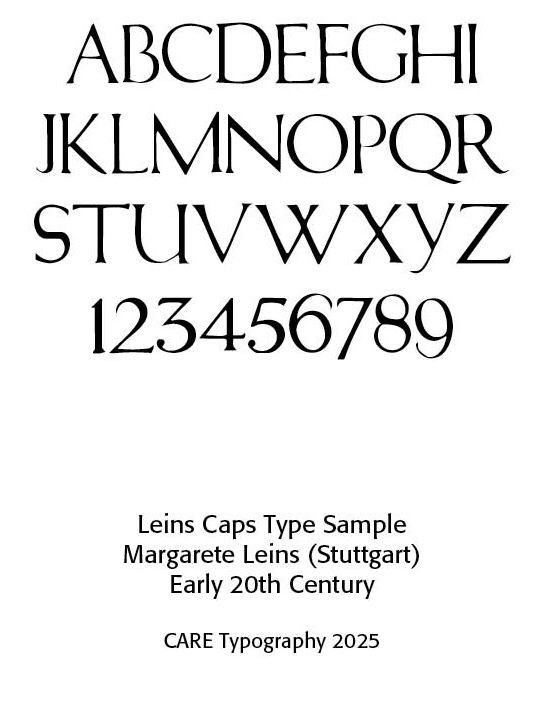

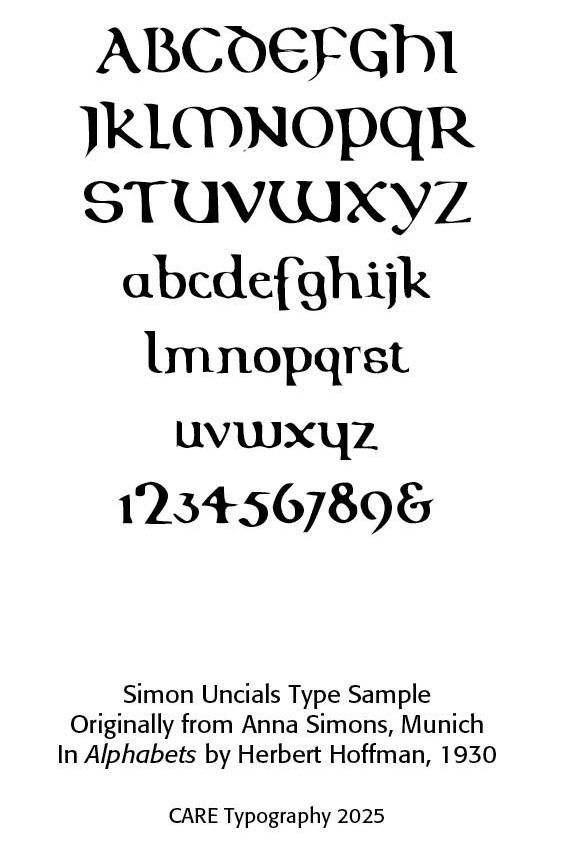

Maria Ballé was one of the first female type designers. While the exact date of her work is not clearly known, references suggest it wa during the 1920s. She created the face called Ballé Initials for the Bauer Type Foundry. She along with Margarete Leins (Stuttgart) and Anna Simons (Munich) were some of the few women typographers of the period. Leins contributed to calligraphy and decorative lettering, participating in the resurgence of handcraft in typography influenced by Jugendstil and the Arts & Crafts movement. Simons translations of Johnston’s work and her teaching helped establish a modern German calligraphic tradition. She influenced Rudolph Koch and others in early twentieth century calligraphic renaissance.

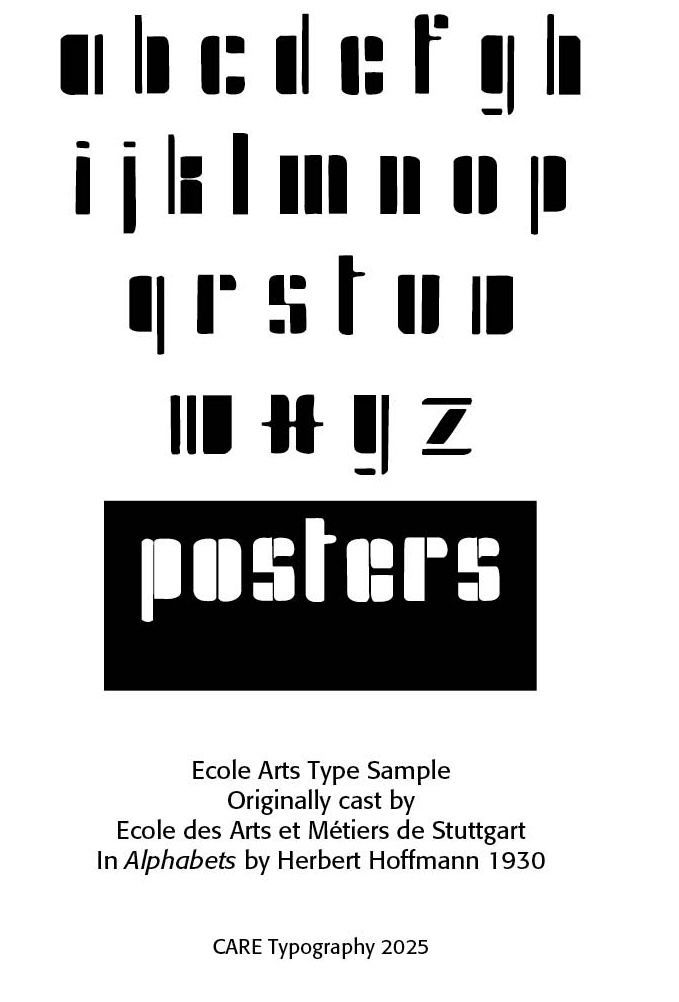

Ecole des Arts et Metiers de Stuttgart (State Academy of Fine Arts in Stuttgart). A public fine art university in Stuttgart, Germany, founded in 1761. By 1950 you could study painting, glass painting, sculpture, free and applied graphics, interior and furniture design (″Innenarchitektur und Möbelbau"), textiles, ceramics, metal and art teaching, and professors included Trude Barth, Otto Baum, Willi Baumeister, Walter Brudi, Rudolf Daudert, Hans Fegers, Eugen Funk, Gerhard Gollwitzer, Peter Otto Heim, Manfred Henninger, Karl Hils, Eberhard Krauß, Hans Meid, Hugo Peters, Karl Rössing, Harmi Ruland, Hermann Sohn, Karl Hans Walter, Hans Warnecke, Kurt Wehlte, Hans Wentzel, Karl Wiehl and Rudolf Yelin. A sample of an early twentieth century art/typography piece highlighting the alphabet is included in Alphabets. (Wikipedia)

Successful Layout & Design