Early German Typography (Part 1)

EARLY GERMAN TYPOGRAPHY

A Historical Sketch (Part 1)

Herbert Hoffmann, Albert Bruckner, Max Hertwig, and Rudolf Koch collaborated on a typographic “atlas” or specimen book titled Hoffmanns Schriftatlas: Das Schriftschaffen der Gegenwart in Alphabeten und Anwendungen (1930) (Hoffmann’s Type Atlas: Contemporary Type Creation in Alphabets and Applications) Also distributed in France under the title Alphabets by Herbert Hoffman and other collaborators by Arts et Métiers Graphiques magazine, it is a specimen of alphabets, initials, monograms, logos and other typographic forms from early German typography. The atlas captures typographic modernism in Germany around that time, including influences of the Bauhaus and the modernist movement. It is considered a rich visual record of type and lettering design in that period, showing both experimental and traditional forms. For collectors and historians, it helps map relationships among type designers, graphic artists, and typographic culture in the interwar years. Alphabets features works by key typographers of early Germany in the 1920s and 1930s including Rudolf Koch, Margarete Leins, Anna Simons, Louis Oppenheim, E.R. Weiss, Ludwig Mayer, Lucian Bernhard and others.

CARE Typography has investigated and revived some of the alphabets in this book, giving alphabetic examples of typefaces long since forgotten or discarded along the way. This blog highlights some of those typefaces along with their creators and later digitizers.

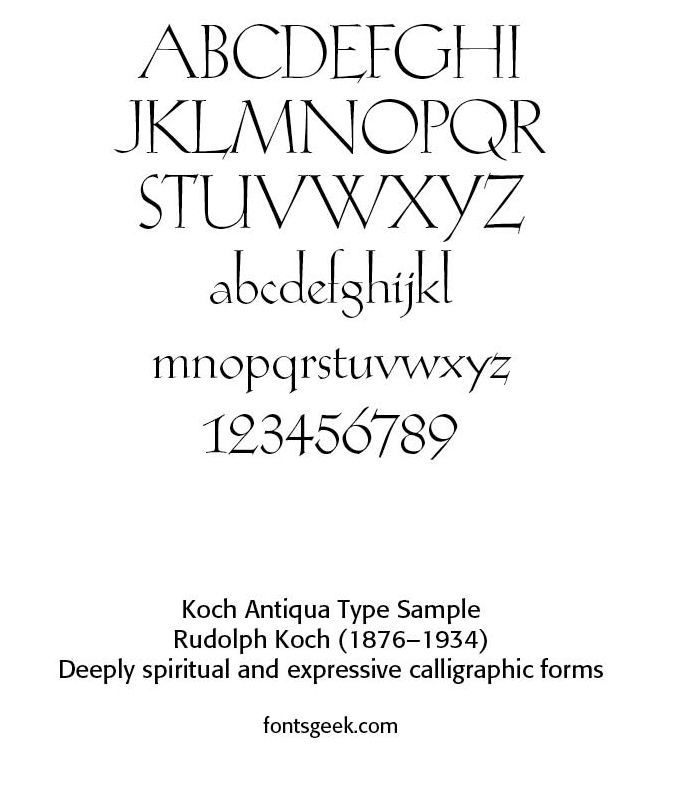

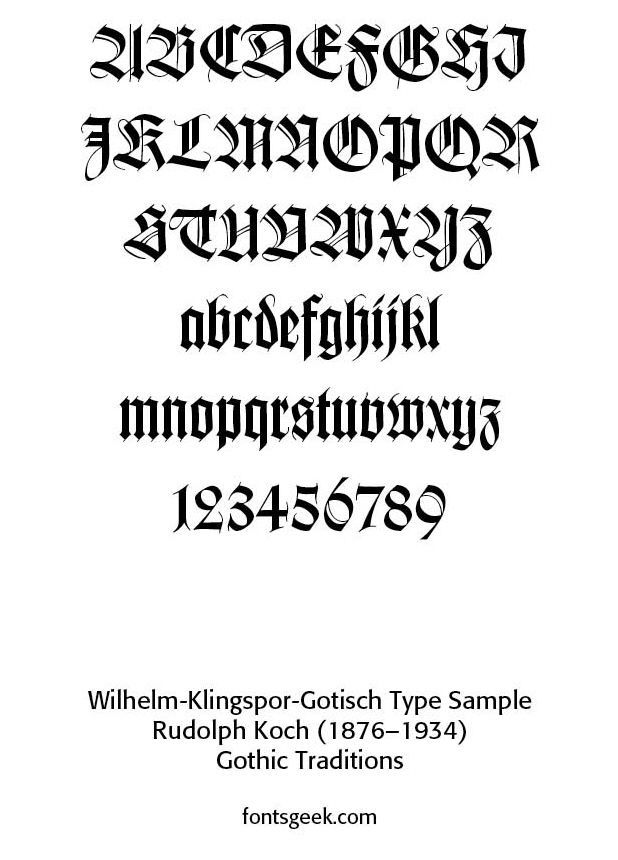

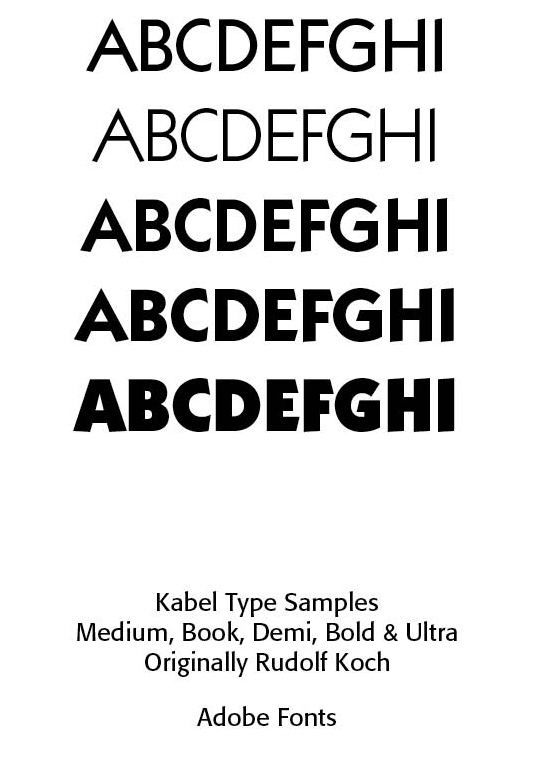

Rudolf Koch (1876–1934). As one of the featured type designers, Koch’s work gives weight and prestige to the anthology. He was a calligrapher, type designer and teacher at the Offenbach School of Design. Renowned for his deeply spiritual and expressive approach to lettering, he blended Gothic traditions with modern, expressive calligraphic forms. His notable typefaces included Kabel, Koch Antiqua and Wilhelm-Klingspor-Schrift as the displays show.

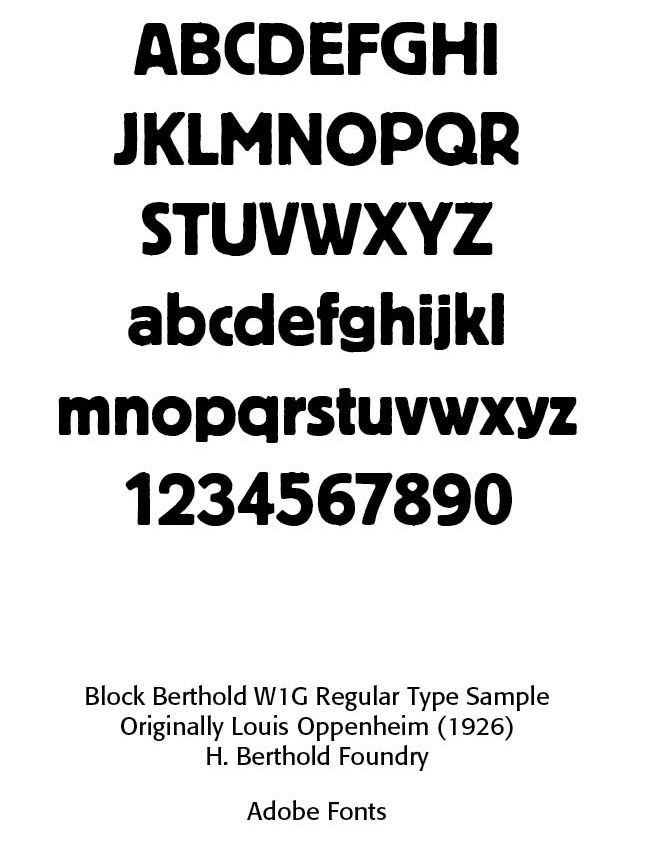

Louis Oppenheim (1879–1936). Oppenheim produced Berthold Block (1926), a heavy, geometric sans serif used widely in advertising pieces. He was strongly associated with early modernist German design, especially display typography. He was a pioneer of expressive and bold typographic forms in commercial graphics. Berthold Block has a chunky design suitable for headings, with short descenders allowing tight line spacing. Typographer Stephen Coles describes it as a “soft but substantial display face with compact dimensions and an organic appearance.”

The original metal design was intentionally “distressed,” matching the effect of worn type. Berthold Block was released in 1908, with Berthold later adding additional weights and styles, along with phototypesetting versions. It was often used by Praktiker and the Whitechapel Art Gallery for branding in the 1970s and 80s. In the late 1970s, Berthold re-released three lighter-weight fonts derived from the Block design as a mini-family named "Berliner Grotesk" for phototypesetting, with the font redraw carried out by Erik Spiekermann.

A variety of digitizations of Block exist, including by Berthold and successor companies and by Bitstream (the condensed weight only). Paratype of Moscow released an expansion with Cyrillic characters in 1997. Matthew Butterick’s Hermes, first released by Font Bureau, and later self-released, is a loose adaptation also inspired by other German grotesque typefaces of the period, adding lighter weights and unicase features. (From Wikipedia) The sample provided is from Adobe Systems 1992 named Block Berthold Regular 400. Block Berthold is a registered trademark of H. Berthold AG.

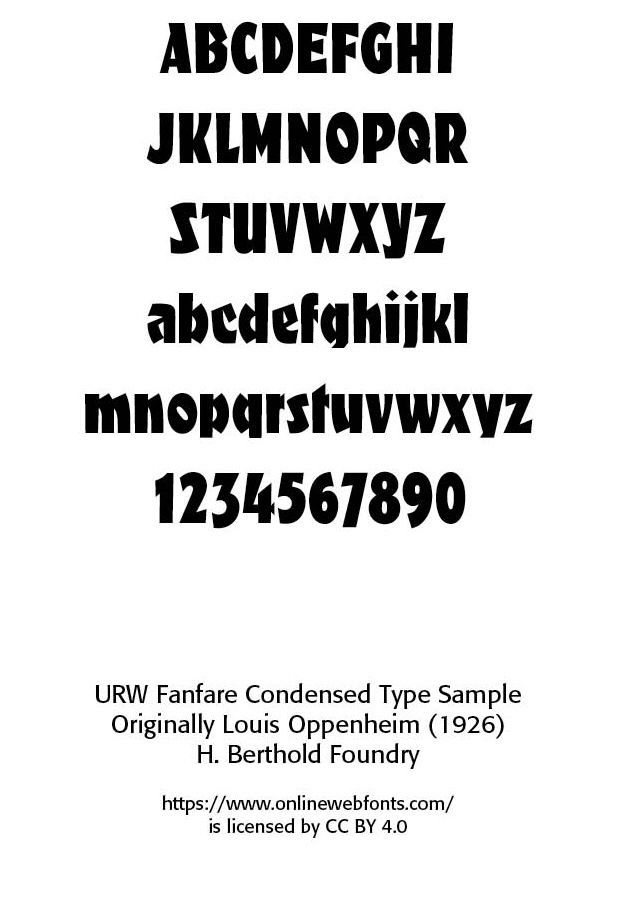

The Fanfare typeface was also designed by Oppenheim and published by the URW Type Foundry and released on MyFonts in 2001. This face also appeared in the Alphabets book.

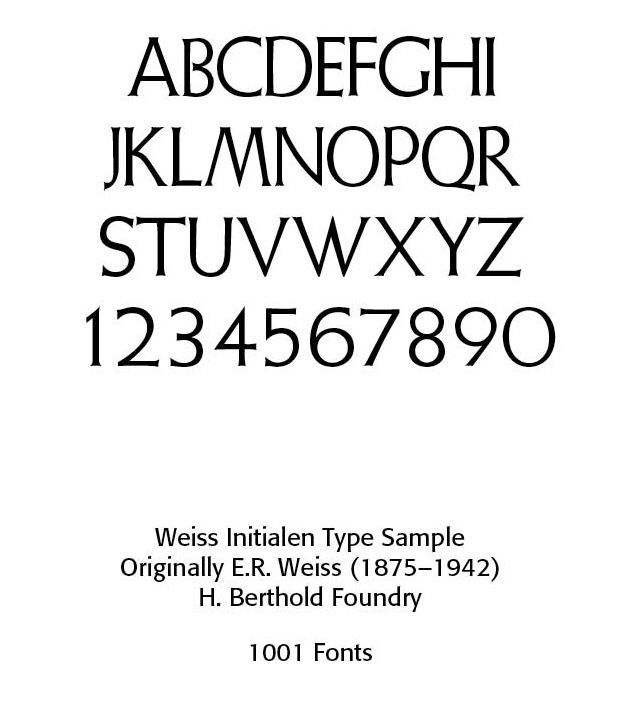

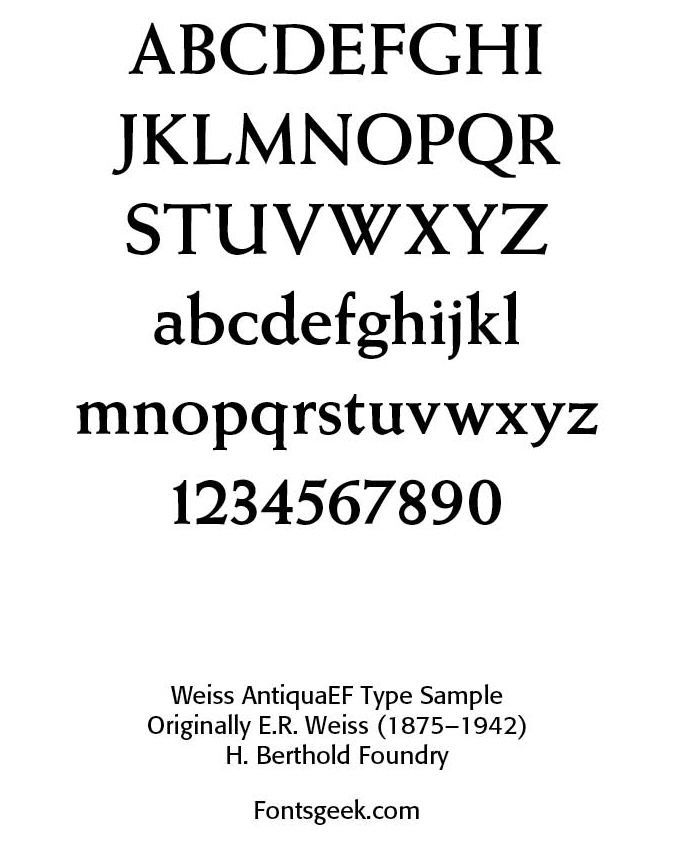

Ernst Rudolf Weiss (1875–1942). Weiss was a type designer, artist and book designer. He blended humanist serif forms with classical calligraphic qualities, creating elegant book typefaces. He was known for his refined and readable type. Weiss Antiqua and Weiss Initialen display how readable and exacting his faces were. Ludwig Mayer (1879–1972) established Ludwig & Mayer type foundry in Frankfurt, which published work by many significant type designers, including E.R. Weiss

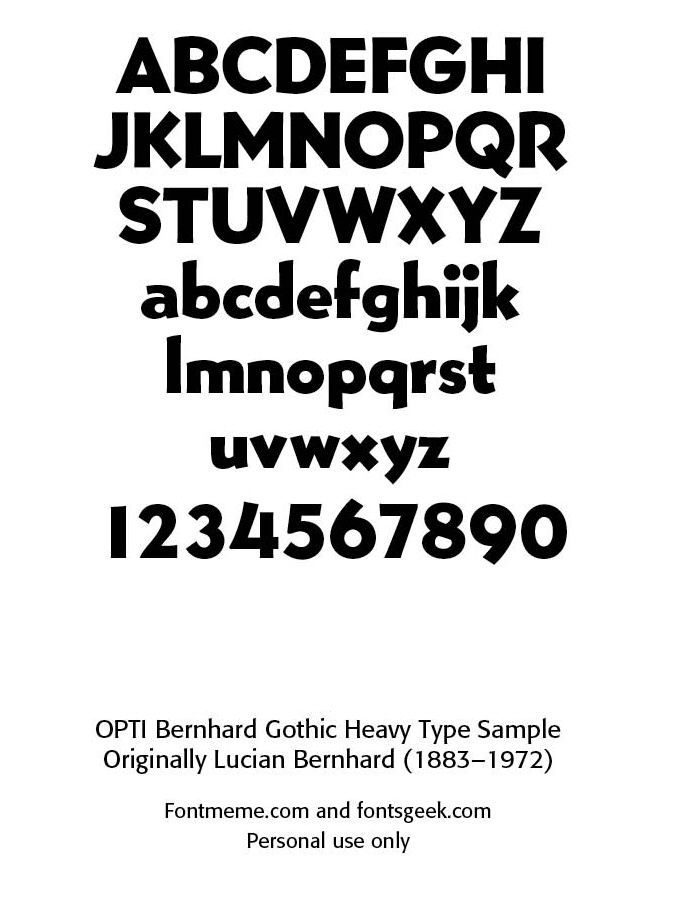

Lucian Bernhard (1883–1972). Bernhard was a graphic and type designer and art director who produced Bernhard Antiqua, Bernhard Gothic and Bernhard Modern. Bernhard Gothic is a family of geometric sans serif faces designed in 1929 for ATF (American Type Founders), with five variations produced in over two years. Bernhard Gothic is more organic and less regular than other geometric typefaces, including Futura and Kabel. The sample shown is OPTIBernhard Gothic Heavy, available from fontmeme.com and fontsgeek.com. OPTI is a label used by Castcraft for digital fonts produced around the early 1990s. Technically, many were likely based on the copies Castcraft had made for phototype. Luc Devroye notes that the company is long defunct with ethical issues having produced fonts of subpar quality (https://luc.devroye.org/fonts-27506.html).

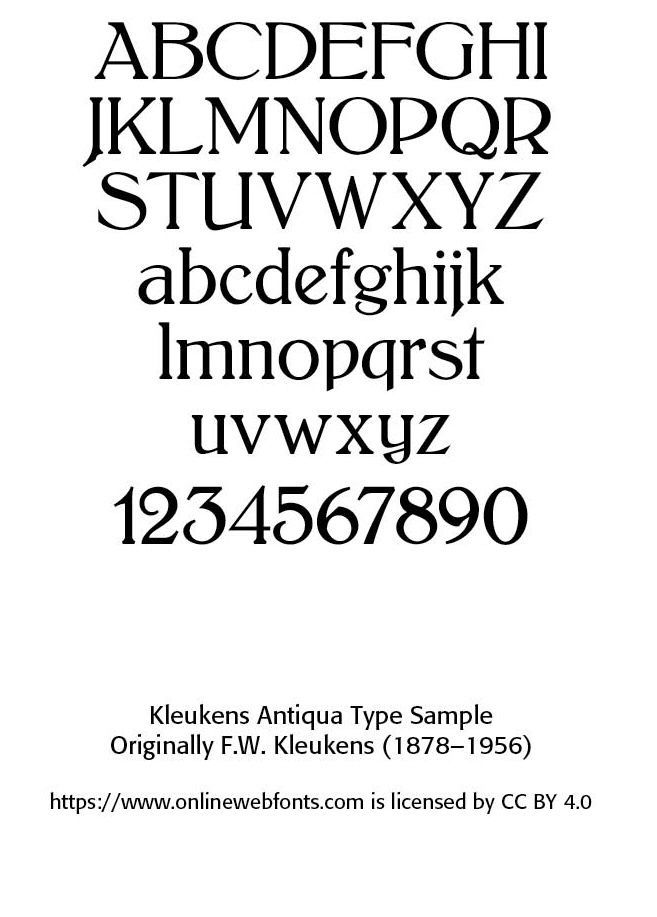

Friedrich Wilhelm Kleukens (1878–1956). Kleukens was a calligrapher and type designer known for elegant type and lettering rooted in tradition but with a modern sensibility. He created Rudina and F.W. Kleukens-Antiqua. He worked closely with Koch and contributed to the German book and type design renaissance in the early 1900s.

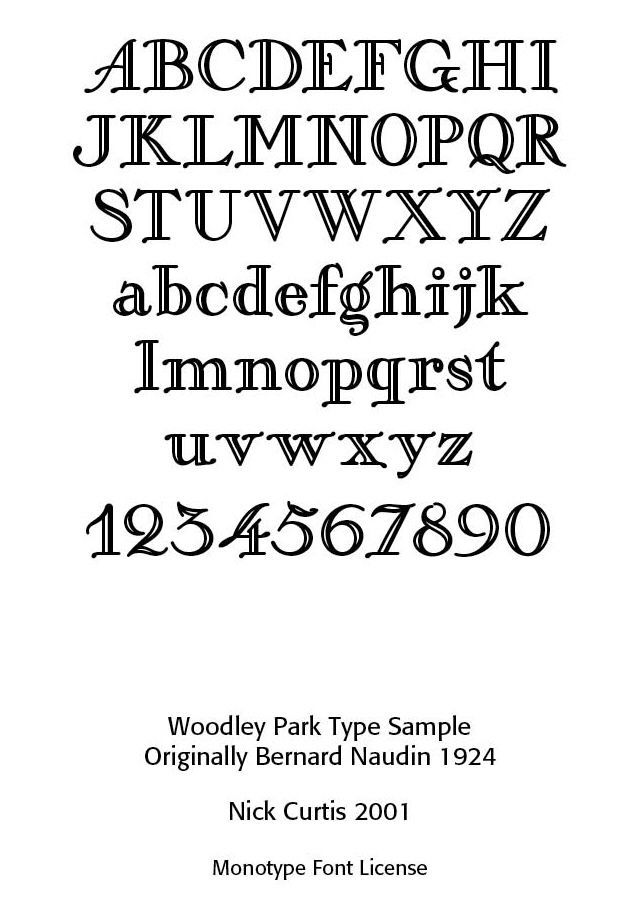

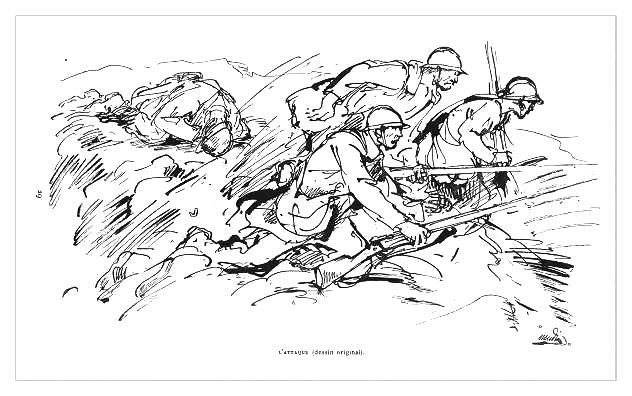

Bernard Naudin (Bernard Étienne Hubert Naudin) (1876–1946). Naudin was a French artist, known mostly for his work as a painter, draftsman, engraver and caricaturist, but he also made contributions to type design. In 1910, Georges Peignot of the Peignot/Deberny & Peignot foundry, asked Naudin to design a new typeface. Working from his own handwriting, Naudin designed and engraved Naudin Roman and Italic as well as Naudin Champlevé.

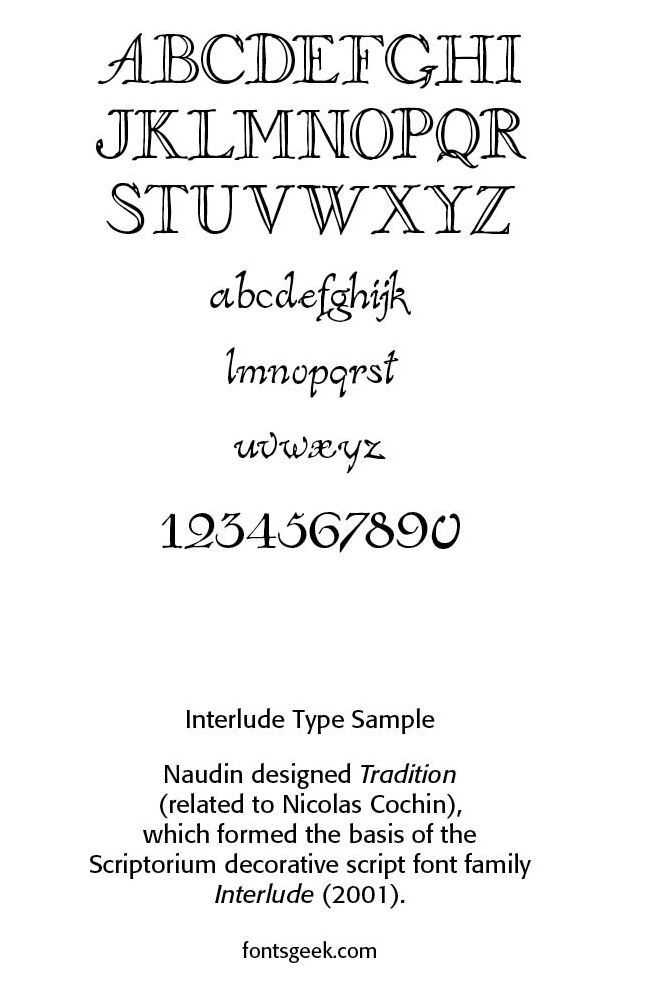

Naudin also designed Tradition, which formed the basis of the Scriptorium decorative script font family Interlude (2001). Champlevé was revived in 2006 by Ari Rafaeli. Woodley Park designed by Nick Curtis in 2001 is also based on Naudin Champlevé. Naudin’s typefaces did not enjoy great success at the time, but other designers have drawn inspiration from his decorative style. His merging of engraving, ornamentation, and artistic illustration into type design gives him an interesting hybrid status of part fine-arts engraver with part typographer.

END PART ONE. In the next installment we shall consider the early German works of Ernst Deutsch, Friedrich Heinrichsen, Benjamin Krebs Nachf, and the three women typographers, Maria Ballé , Anna Simons and Margarete Leins. We shall also note the Ecole des Arts et Metiers de Stuttgart.

Successful Layout & Design