Do's and Don't's in Using Type

From The Elements of Typographic Style

In the world of precise and well-defined typography, there is probably no more useful and thorough work than Robert Bringhurst's The Elements of Typographic Style. Although casual writers and office personnel pay little attention to such things, glaring examples of misused typefaces and writing can be found everywhere. A cure to such ignorance and oversight can be found in this 255 page masterpiece on what characters to use when and how. One commentator notes that "it may be hard to imagine that one could write 600 words about the 'lowly' hyphen, but Bringhurst does so, and makes reading it interesting." (Harry Edwards, Review of Bringhurst, March-April, 1993 in Aldus Magazine)

The key to excellent and well-defined typography is Bringhurst's principle that "Typography exists to honor content." Chapters on "Rhythm and Proportion," "Harmony and Counterpoint, "Shaping the Page" and so forth give time honored attention to what most casual writers ignore and of which they are unaware. Some examples and some words of advice can enhance and make your writing and posts and newsletters much more readable and professional.

Example #1 — The Widow and Orphan. Orphans are created when you have isolated lines of multi-line paragraphs ending a page. "The stub ends left when paragraphs end on the first line of a page are called widows." (41) Giving such lines at least one additional line or by exporting or importing single lines from the preceding or following spreads can avoid widows and complement forlorn isolated lines at the end of a page. This typographic rule is broken unabashedly and incessantly by even many well-trained journalists and newspapers. Spending more time rewriting the text so that orphans and widows don't exist is the solution, though it may be time-consuming to quick turnaround jobs.

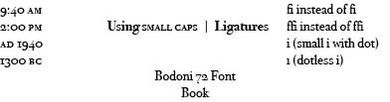

Example #2 — The use of AM, am, PM, pm, or A.M. or P.M. or a.m. or p.m. and such should be discontinued. Instead, spaced small caps should be used as in 42 bc and ad 200 or 3:00 pm or 9:00 am. But regular caps are used for JFK or H.C. Shank, and note there is no space between the H. and the C. (And there should be a small space between the small caps that cannot be written in this digital post, but see the examples below.) Bringhurst points out that "The better digital foundries now offer a wide selection of fonts with text figures and small caps. These are often sold separately [but not soon anymore due to Adobe's new typeface developments — See last post] and involve extra expense, but they are essential to good typography. It is better to have one good face with all its parts, including text figures and small caps, than fifty faces without." (45)

Example #3 — The use of slanted italics instead of true italics, or digitized bold for true bold. Cheaper faces, and often sans serif faces, have what are called "slanted" figures for italics, such as Arial Italic, which is just a slanted face instead of true italics. So, for instance, you will see text emphasized like this, when the typeface used should be emphasized like this. The difference is amazing and outstanding. Again, this requires a font with true italics included in the font itself, rather than a digitized slant produced by electronic means. Such constraints should also be used for true Bold instead of just digitized bold in font use. So, for instance, the Brisco Pro Typeface uses Brisco Pro Regular, Brisco Pro Light, Brisco Pro Italic, Brisco Pro Bold and Bold Italic, Brisco Pro SemiBold, SemiBold Italic, and Brisco Pro Medium and Medium Italic. Again, one may wonder why this is important. It is where function defines form in typography. If I want something to stand out, I might use an Ultra Bold font, like Gill Sans Ultra Bold, instead of regular Gil Sans Bold. See the difference?! An Ultra Bold font, however, is an extra face usually not available in the regular four-face series of regular, italic, bold and bold italic.

Example #4 — The use of overlapping letters rather than normally accepted ligatures. Modern typesetting and even modern word processors have ably given writers what are called ligatures — the proper combination of letters in words like f plus f, and f plus i, and f plus l, and f plus f plus i, and f plus f plus l. Most fonts include such ligature automatically, but if they do not, you can have overlapping and confusing letters giving different meanings to different words. Bringhurst mentions that "in Turkish, i with a dot and i without, are two different letters. A typeface whose lowercase f disguises the difference between the two forms of i is therefore, for Turkish, an unacceptable design." (48) See example below.

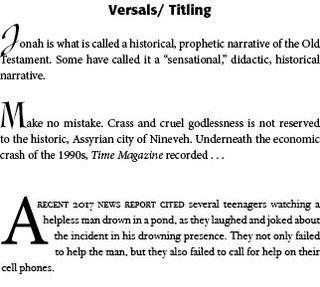

Example #5 — Drop Caps, Fleurons and Opening Paragraphs. At chapter beginnings, drop caps are often used to introduce and draw the reader into the text — "But the most traditional method of marking the start of the text, inherited from ancient scribal practice, is a large initial capital or versal." (61) They can be indented, centered, or flush left with the rest of the text. They can hang in the left margin. "They can be set in the same face as the text or in something outlandishly different." (61) Or in older texts a "fleuron" or typographical ornament can be used to draw attention to the text — such as sdhj (International Font). Sometimes they are in a different color than the regular text, such as traditional red — sdhj. Bringhurst provides a page of examples (62) of various titling and drop caps. Care Typography has a specialized set of typographical ornaments, especially designed for churches and ministries. See sample below. Page layout programs, like Adobe's InDesign, provide a convenient and trouble free way to use drop caps or titling caps in an opening paragraph.

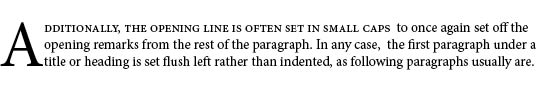

Additionally, often the opening sentence or a few words will be set in small caps to once again set off the opening remarks from the rest of the paragraph. In any case, the first paragraph under a title or heading is set flush left rather than indented, as following paragraphs usually are.

Successful Layout & Design