BLOG

Blog

By Carl Shank

•

19 Apr, 2024

My wife and I took a trip to Washington, D.C. to the Museum of the Bible. This is an amazing place with collections of Bible history, Bible characters and Bible applications for the interested viewer. We especially toured the fourth floor that contains more than 600 artifacts and 50 media programs introducing us to the Bible's history, from handwritten scrolls to mobile devices. As a theologian and typographer, I was interested in not merely the history of the printed Word of God, but also how it was printed through the ages. I was especially fascinated by the delicate and intricate versals, those opening letters and flourishes to the printing. I have gathered a number of the versals and cleaned them up using Adobe Photoshop for display. The pages below contains some of the oldest versals used in Bible typography and printing. They are historically valuable and worth our time and effort in viewing and understanding. Enjoy them!

By Carl Shank

•

28 Mar, 2024

About Paper In a blog last year (March 9, 2023) I wrote about “Which paper?” Since that blog I came across an interesting archival copy of National Geographic Magazine (March 1997) on “The Magic of Paper” by Jon R. Luoma.(1) He added to my knowledge about paper, its origins and its lasting qualities, along with modern problems that paper production has raised. This blog is therefore a revision of my original blog on paper. Importance of Paper Luoma states, “On paper the lessons of history and the fire of human genius have blazed across space and time—the notes of Mozart, the words of Shakespeare, the sketches of Picasso, the wisdom of Gandhi. Words on paper changed the way people thought. Martin Luther went so far as to call printing ‘God’s highest and extremest act of grace.’” He goes on to note that paper and printing rescued Europe out of the Dark Ages, especially with Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press. (For a summary and pictorial history see Blog on “Typography: A History of Machines, March 12, 2023). Luoma says that “just 50 years after Johannes Gutenberg invented his printing press in the mid-15 th century, more than six million books had been published on law and science, politics and religion, exploration and poetry.” A third of a billion tons of paper are produced each year by paper producers across the world. Indeed, as of 1997, “in the U.S. alone a 170-billion-dollar industry makes enough paper each year for two billion books, 24 billion newspapers, and some 372 billion square feet of corrugated cardboard.” In modern day printing, a large part of using type correctly, persuasively and aesthetically pleasing depends upon the kind of paper used. You do not print a wedding invitation on any cheap copy paper that you might have at the office copier. You want to submit a resumé and want it to showcase your character and standards. The paper choice is important for this. You want a colorful, playful, shiny paper for a kid’s party. What paper should you use? While many have gone the route of digital printing and digital typography, for Facebook and other social media use, others have seen the continued need to choose the right paper at the right time for the right job. But with the plethora of papers available, which one(s) do I choose? Origins of Paper The invention of paper can be traced back to ancient China, where it was first developed (according to AI from ChatGPT) during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD). Tradition has it that centuries before Gutenberg, Ts’ai Lun created paper from hemp, tree bark, rags and fishnet in AD 105. Prior to this, various materials were used for writing, such as bamboo, silk, and animal skins. However, these materials were expensive and difficult to obtain, so the Chinese began experimenting with other materials. The earliest known paper was made from mulberry bark, hemp, and rags. The fibers were pounded into a pulp and then pressed and dried into sheets. This process allowed for the production of large quantities of paper at a much lower cost than other writing materials, making paper accessible to a wider range of people. Luoma notes that long before Gutenberg, “the Chinese invented movable type. They were the first to make paper money, toilet paper and paper books. It was forbidden even to step on a piece of paper with writing on it.” The art of washi, handmade paper, existed, and still does, among the households of many Japanese. Indeed, they have intermingled their faith and lives with paper. The writer and poet, Fu Hsien, noted this about fine paper — “Luxury but at a small price / Matter immaculate and pure in its nature / Embodied in beauty with elegance incarnate / Truly it pleases men of letters.” The knowledge of paper-making eventually spread to other parts of the world, including the Arab world and Europe. During the Middle Ages, paper mills were established throughout Europe, and paper became an important commodity for trade and commerce. In Gutenberg’s time, printers used paper made of hemp and linen rags, thus ensuring the survival of great works for hundreds of years. While nonacidic paper is used today in printing, in the 19 th century, fiber from trees was cemented together with lignin, which eventually oxidizes, turning the paper brown. This was enhanced by acid sizing added during the production process. This is why books and papers from that era are more and more difficult to find and preserve, and thus the modern need for digital storage and retrieval. Some Definitions About Paper Paper Sizes . The standard known U.S. size paper is 8.5 x 11 inches, in either Portrait or Landscape mode. Legal size is 8.5 x 14 inches, used for contracts within legal, real estate and accounting professions. Tabloid or ledger size is 11 x 17 inches, used in offices for diagrams and documentation requiring larger drawings, like architectural and CAD drawings. To many people worldwide, excluding North America and Canada, the most familiar paper size is A4 (a familiar 210 mm x 297 mm). It is commonly used for letters and correspondence in the UK and it is the standard paper size for most home printers. The A4 size paper measures 8.27 x 11.69 inches, only slightly larger than the close equivalent to U.S. letter size 8.5 x 11 inches. Most printers and copiers in this country are preset for letter sized paper. Paper Weight & Thickness. Paper weight and thickness reveal the sturdiness and often opaqueness of the stock, with weightier paper providing more durability than a thin weighted paper stock. Paper is measured in points, where one point equals .001 inch, so that 10 point paper is .01 inches thick, 30 point is .03 inches and so forth. But paper weight can also be measured in GSM (grammes per square meter), so that fine art papers are usually made in the range of 120 gsm to 850 gsm. Drawing papers are usually 130 gsm and the Snowdon Cartridge papers are 300 gsm. Thicker paper can withstand erasing and mark making. Such paper is ideal for printing processes including etching, silkscreen and offset lithography. Oriental papers tend to be lighter in weight, such as Japanese papers made with long fibers and great strength, often an artisan skill passed from generation to generation. Cover stocks are at the higher end of the weight spectrum and feel like thin cardboard. A ream of paper is 500 sheets, and office paper is usually sold in reams. Peter Giffen (2) notes that in the United States, the weight of paper stocks is usually done in pounds, which is the actual weight of 500 sheets of the “basis size” of the paper in question. Since the basis size may vary, comparing paper weights can be hard to do. For example, a 28-pound multipurpose paper is probably not the same weight or thickness as a 28-pound premium or cardstock paper. Standard copy paper is rated at 20 pounds and sometimes 24 or 28 pounds. I use 28 pound paper in my color printer for sharper images and no text see-through on the back of a sheet. Copiers use 20 pound paper as the cheapest stock for most office projects and memos and day to day use. Paper Brightness & Opacity . Brightness refers to the amount of light that reflects off a sheet of paper and opacity refers to whether one can see the writing on the other side of the sheet. One hundred percent opacity (100%) means that no light shines through and zero percent opacity (0%) is see-through tracing paper. Black text tends to stand out on most paper brightness levels, so text documents only need an ordinary level brightness in the 80s and low 90s when measured on a scale of 100. A colorful design or fine-art reproduction may require the highest level of brightness. Paper Types . There are generally five common paper types — matte, glossy, silk, bond and cardstock. Matte paper stock is generally used for text-heavy leaflets and flyers, with easy to read ink and sharp black and white contrasts. Glossy paper is used often for colorful flyers, leaflets, menus and other projects requiring sharp images. Such paper gives a high quality, professional appearance. Silk paper is soft to the touch and fills magazine pages, portfolios and other high quality printing. Bond paper is the durable traditional stationery paper for documents that you want to last a long time. Cardstock is used for business cards, booklets, leaflets and can stand extra wear and tear and constant use. Inkjet papers are specially designed to absorb the inks used in the printing process. Laser paper can withstand the heat (from the printer’s fuser) of laser printing. Photo paper can be matte or glossy and is used for printing photographs. Bond paper has a high content of cotton rags or cotton textile fibers in its composition. The name goes back to the late 19th century when such paper was used to print government bonds and other official documents. Bond paper today is often used for stationery, letterhead and drawing paper. The best archival grade paper(3) is made from 100 percent cotton which gives a strong, acid free material which lasts longest, and is the most resistant to discoloration and deterioration. The interweaving of the fibers gives paper its inherent strength, which is improved by the use of ‘size’, the paper being too absorbent on its own, is prone to disintegrating when too wet. Saunders Waterford, Somerset papers, Arches and some Fabriano papers, which are all 100 percent cotton, are sized to respond well to water based media. Japanese papers have a subtle beauty all of their own; generally very light weight they are made with long fibres and have great strength. “Acid-free” indicates the paper is made without rosin and alum sizing which would make the paper acidic. Acid-based paper is prone to fade over time and atmospheric conditions. Microscopic impurities on or in the paper can in time create little brown marks, called “foxing.” Specialty papers can be especially environmentally-friendly due to materials used or how fast they biodegrade. Recycled paper according to the ftc (Federal Trade Commission) is “a paper that only contains 100 percent post-consumer recovery fiber. If less that 100 percent the paper is called recycled-content paper.” Recycled paper can be made from pre-consumer materials, recovered from the leftovers in the manufacturing process, or post-consumer waste, gathered from used newspapers, for instance. Premium paper has all the top attributes of weight, coating, brightness, opacity and material, making them good for presentations and quality print jobs. Such paper is made from a blend of wood pulp and cotton (usually 75 percent and 25 percent) and has a luxurious feel and is made to last for archival projects. Premium paper is often used for resumés, portfolios, quality reports, business proposals, announcements and high-level presentations. They have great brightness and durable weight. Midori, or MD paper, is Japanese paper with whisper thin texture. It is lightweight and smooth, yet there is no bleed through for fountain pens. It can be used for notebooks, writing letters, or for calligraphy. Calirefontaine is French classic thick and opaque smooth, lined paper. Classica paper is designed and made in Italy, with a soft, almost fabric-like feel and is used for stationery sets. Problems With Paper Environmentalists have long claimed that the paper business denudes forests and pollutes air, land and water by poisons like dioxins as an industrial by product. The truth is, however, that less than 9 percent of the total timber harvest in the U.S. is pulpwood used for paper production. Old manufacturing methods of paper production leaked chemicals into nearby streams and rivers, chemicals that came from bleached pulp with chlorine, reacting to form organochlorines, which eventually work their way into the fatty tissues of fish and other creatures. Modern industrial methods of paper production use a series of tanks to close the water loop so that harmful chemical discharges into area streams is greatly reduced. Also, other bleaching methods are used to reduce organochlorines dramatically. Again, Peter Giffen is helpful here — “Sustainable papers come from carefully controlled forests that are replanted and renewed. They meet specific environmental standards, helping users support practices that better protect forests and the environment. Some papers boast an fsc certification. The Forest Stewardship Council is a widely respected not-for-profit organization that seeks to protect the world’s forests by monitoring and improving timber production. The fsc has worked with key players in the lumber industry to inspect and track timber and pulp through production chains, ensuring that woodlands are managed sustainably. Any paper products certified by the fsc are created with sustainable practices. While some businesses might be hesitant to use recycled paper since its texture and quality can differ slightly from virgin paper brands, fsc-certified products are virtually indistinguishable. Generally speaking, recycled paper costs more than unrecycled paper because there is more demand for the latter, and recycled paper costs more to process.” Hammermill Papers is an example of a modern paper making company seeking to tackle paper making problems. Back in 1898, five years before the Wright brothers took off at Kitty Hawk, three brothers from Germany founded the Hammermill Paper Company in Erie, Pennsylvania. As immigrant success stories go, the Behrend brothers rank right up there in the history of American business. Especially since, more than 120 years later, Hammermill paper is still being made in America. unlike imported papers, the paper mills that produce Hammermill are strategically located near sustainably-managed forests. That means shorter transportation distances, which lead to less fuel usage, reduced emissions, and a healthier planet. But the biggest benefit of being made in America is this: Hammermill paper helps to preserve American forests. This may sound counter-intuitive, but the claim is a sound one. First, our entire business model depends a sustainable supply of paper fiber from healthy forests. And second, 90 percent of Hammermill paper fiber is sourced from sustainably-managed, privately-owned forestland.(4) Which Paper Should I Use? While most offices order and use the cheapest 20-pound copy paper available for almost anything they print and copy, care should govern the choice and use of paper appropriate for the job or task at hand. Writing paper should be good quality stationary. Use premium paper. Write on white, ivory or cream letter paper. This will give the recipient the feeling of quality and that your letter is of importance to them. If you are not using headed paper, ensure your full address is written in the top right hand corner of the letter. Notepad paper can’t be too thick or too thin, since flimsy paper tears too easily and thick paper is too bulky. MD paper can be used if bulky space is an issue. Instead, opt for a happy medium with 70 pound opaque notepad paper that offers a smooth writing experience and enough stability to hold up to vigorous note-taking.(5) The choice of paper for typesetting and printing depends on several factors, including the printing method, the purpose of the printed material, and the desired aesthetic effect. Generally, papers that have a smooth, even surface and good opacity are considered best for typesetting, as they allow for crisp, clear text and images. If you are printing on both sides, front and back, you do not want the type to show through. I regularly use a 28 pound high quality bright paper for layout and printing work. PaperDirect is a good resource for all kinds of paper (https://www.paperdirect.com). Notes 1. Jon R. Luoma, The Magic of Paper in National Geographic Archive, March 1997. 2. Peter Giffen in https://www.officedepot.com/l/ideas-center/buying-guides/paper-buying-guide. 3. According to https://www.pegasusart.co.uk/types-of-art-paper.irs. 4. From the Hammermill website at https://www.hammermill.com/blog/hammermill-paper-is-made-and-remade-and-remade-in-america. 5. https://www.psprint.com/resources/notepad-printing-techniques/

By Carl Shank

•

23 Mar, 2024

Printers Maxims & Other Notes Printers and typesetters can gain much wisdom from older printers. The Printers’ Handbook of Trade Recipes, Hints & Suggestions Relating to Letterpress and Lithographic Printing, Bookbinding, Stationery, Engraving, Etc. , compiled by Charles Thomas Jacobi, London, 1891, gives what is called “Maxims for Printers.” These maxims and many others have guided the printing trade for many years. They distill the wisdom of centuries of printing and typography. We would do well to heed such advice. 1. It is better to remain idle than to work at a loss. 2. Genius is as rare in printing as in any other art. 3. Legitimate competition is a sign of life and health. 4. Do your work carefully, striving for constant improvement. 5. Follow copy, provided it is good, and never copy anything bad. 6. You cannot be a successful printer if the imprint of care and study is not upon brain and hands. 7. Preserve all specimens of good work that come into your possession, and spend your leisure time in their study. 8. Unless an apprentice is possessed of an ambition and determination to excel, the chances are that he will always be but a poor workman. 9. Skill in business, a well-earned reputation for uniformly superior work, a good financial credit, promptness, honorable and liberal dealing, correct and steady personal and business habits, are absolutely necessary concomitants of success. 10. No matter how good a printer you are, you will learn something every day; and in every job you do for a customer, study how you can improve it next time. Never let a poor or carelessly executed job go out of your office, no matter even if, by mistake in “estimating,” or for any other reason, you may lose money on this particular one. 11. Study the work of first-class printers. A skilled workman has expended time, thought, and labor in its production. 12. It is not the grace or beauty of a single line that produces the result sought. The specimen must be judged as a whole. 13. Never curve a line where it would look better straight. 14. Do not crowd a job to put in a flourish or ornament. 15. Elaborate borders can only be used effectively by first-class workmen. 16. A plain rule border, with a neat corner, is more effective than a display border on a small card. 17. Ornament has to be kept strictly within the stern chasteness of taste, and permits of no extravagance of detail. 18. Ornament should always be subservient to its proper use. Any superfluity or preponderance destroys the proper effect. 19. Better do a good, plain job in black ink and one style of type, than an outrageous combination of fantastic ornaments in the glowing hues of the rainbow. 20. The use of ornaments requires a cultivated taste. They were intended to “light up,” not smother; to give an “airy grace,” not detract; to do away with “monotony,” not make a dreary waste. Color Blindness The land, especially during the holiday season, is flooded with abominations of tint and taste, with miserable chromos and calendars that are a disgrace to the art. When will craftsmen learn to avoid the delusions and pitfalls of color, and assert the strict taste embodied in black and white? Zebra-striped and rainbow-illuminated monstrosities will ever be a plague to the inventor, and are worthy only of some demented members of the paste-brush brigade. Hints on Composition Understand your take fully before leaving the foreman or copy hook. Time spent in this way is profitably invested. At least read through the outlines of the job. If pamphlet or book-work, the reading of the first page or two will be sufficient. Determine upon display lines. Spelling, style of punctuation, capitalizing and paragraphs, should be according to usage of establishment. If possible, absorb the subject of your take; it will render work more engaging. The Origin & Use of Italic The form of Roman now known as Italic was originally called Aldine. The first volume printed in this character had the capitals with their stems upright like those of the current round hand. These first editions were the works of Virgil, printed by Aldus Pius Manutius, in 1512, and it is known that this celebrated printer made use of a manuscript text entirely copied by Francesco Petrarca. Thus, it is said, that Manutius desiring to pay public and reverent homage to the author of the Canzoni, appropriately wished a hanging character cut in imitation of his writing, entrusting the design and the cutting to a skilled artist, one Francesco de Bologna. But the fashion of these editions in cursive italic type lasted only a short time, having been imitated by foreign printers in a careless and illegible manner. The cursive character was at that time known both in Italy and outside of the country under the name of Aldine, but later the title of cursive was given to it from the writing of the Roman Chancellery, called cursiveti seu cancellarii ; a title which in Italy has superseded every other. Other information on Italics can be found in Robert Bringhurst, The Elements of Typographic Style — “Early italic fonts had only modest slope and were designed to be used with upright roman capitals. There are some beautiful fifteenth-century manuscript italics with no slope whatsoever, and some excellent typographic versions, old and new, that slope as little as 2°or 3°. Yet others slope as much as 20°. Italic and roman lived quite separate lives until the middle of the sixteenth century. Before that date, books were set in either roman or italic, but not in both. In the late Renaissance, typographers began to use the two for different features in the same book. Typically, roman was used for the main text and italic for the preface, headnotes, sidenotes and for verse or block quotations. The custom of combining italic and roman in thesame line, using italic to emphasize individual words and mark classes of information, developed late in the sixteenth century and flowered in the seventeenth.” (Robert Bringhurst, The Elements of Typographic Style (Hartley & Marks, 1992 edition, 54) Bringhurst goes on to comment on font use — "Don't use a font you don't need. The marriage of type and text requires courtesy to the in-laws, but it does not mean that all of them ought to move in, nor even that all must come to visit. Boldface roman type did not exist until the nineteenth century, and bold italic is even more recent.Generations of good typographers were quite content without such variations. Font manufacturers nevertheless now often sell these extra weights as part of a basic package, thereby encouraging typographers - beginners especially - to use bold roman and italic whether they need them or not." (Bringhurst, 52) “Some of what a typographer must set, like some of what any musician must play, is simply passage work. Even an edition of Plato or Shakespeare will contain a certain amount of routine text: page numbers,scene numbers, textual notes, the copyright claim, the publisher's name and address, and the hyperbole onthe jacket, not to mention the passage work or background writing that is implicit in the text itself. Butjust as a good musician can make a heart-wrenching ballad from a few banal words and a trivial tune, so thetypographer can make poignant and lovely typography from bibliographical paraphernalia and textual chaff.The ability to do so rests on respect for the text as a whole, and on respect for the letters themselves. Perhaps the rule should read: Give full typographical attention especially to incidental details.” (Robert Bringhurst, 24)

By Carl Shank

•

15 Mar, 2024

About Printers’ Marks — Highlighting Crosses Printers’ Marks are symbols or logos that have been used as trademarks by early printers, starting in the fifteenth century. Before the introduction of copyrights, printers’ marks legitimized a printer’s work. Copyright legislation would not be introduced until the eighteenth century. Such marks usually appeared on the last page of a printed work. The first known mark can be found on the Mainz Psalter, produced by Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer in 1457 (See Example below). This mark depicted two shields bearing a saltire, a diagonal cross and a chevron surrounded by three stars. At the outset these were marks of the printer, but the practice was gradually adopted by publishers. In early works a statement at the end listed the date of completion and the location. Sometimes the name of the printer or scribe or their initials were included. In printing and typography this is called a colophon , derived from the Greek word κολοφών, meaning summit, or finishing touch. The printer’s mark was added and gradually moved to the title page of the book. The earliest marks were simple designs produced by using a woodcut stamp. Maggie Patton in her excellent introduction to printers’ marks notes that “the design of a printer’s mark used visual puns, wordplay or sometimes a rebus, a puzzle combining illustrations and letters to depict a motto or printer’s initials. Sacred symbols, the cross and the orb, real and mythical animals, heraldic symbols, and scientific instruments were used in thousands of combinations. The sixteenth century was the highpoint for printers’ marks, when lavish illustrations incorporating a printer’s mark decorated title pages. Many famous images and symbols originate from printers’ marks. The design used by Venetian printer Aldus Manutius depicts a dolphin wrapped around an anchor. The printer’s mark used by French printer Robert Estienne shows a man standing by an olive tree, symbolising the tree of knowledge. Christophe Plantin, in Antwerp, used a pair of compasses held by a hand extending from a bank of clouds, the compass points signifying labour and constancy.” [1] An extensive work on printers’ marks written by William Roberts in 1893 ( Printers’ Marks: A Chapter in the History of Typography ) showcases a number of printers through the centuries and their trademarks. His work has been reproduced by Project Gutenberg as an eBook.[2] Printers’ Marks: The Crosses There is an extensive use of the symbol of a cross on many of the earliest printers’ marks. In researching and digitally reproducing these marks, as a typographer and theologian, I find Roberts’ discussion of this phase of printers’ marks unfortunate and demeaning. He says that “there are many points which will forever remain in the region of doubt and obscurity. Tradition is proverbially difficult to eradicate; and all the glamour which surrounds the history of the Cross, and which found expression in, among other popular books, the Legenda Aurea, maintained all its pristine force and attractiveness down to the end of the sixteenth century. The invention of printing and the gradual enlightenment of mankind did much in reducing these legends into their proper place.” [3] He goes on to question the marks with these words — “Why at the extreme top of the cross is the lateral line formed into a sort of triangular four? Why, without this inexplicable sign, has the cross a number of cyphers, two, or even three, cross-bars? Why should the tail of the cypher 4 itself be traversed by one or sometimes two perpendicular bars which themselves would appear to form another cross of another kind? Why, among the ornamental accessories, do certain species of stars form several crosses, entangled or isolated? Why, at the base of the cross is the V duplicated?" All these are problems which it would be exceedingly difficult to solve with satisfaction.” [4] In my own study and exploration of these cross marks, what I have found is that the symbolism of the cross at the top with a globe and initials at the bottom indicated a humble submission to the Lordship of Jesus Christ over the earth and its inhabitants, inclusive of the printers themselves. Many of these symbols were crafted by religious men who, instead of capitulating to the times, wanted to express their faith stance for all to see. I have attached below a carefully crafted redrawing of many of these cross printers’ marks, made available by CARE Typography as a typeface. (See Below) Thus, the cross mark, as Roberts has to point out, is “a very striking proof of what M. Delalain calls "la persistance de la croix." It has appeared in all forms and in almost every conceivable shape. Its presence may be taken as indicating a deference and a submission to, as well as a respect for, the Christian religion, and M. Delalain is of the opinion that the sign "eu pour origine l'affliation à une confrérie religieuse." [5] The earliest printer’s mark by Fust and Schoeffer in 1457 indicated a diagonal cross. It was placed as a colophon at the end of the Psalter printing, the second work of Gutenberg. The Somachi Fathers operated a press, being a Catholic Order founded for men in Italy in the sixteenth century. Providing staff for boys’ homes and serving 95 parishes, as well as other ministries, their printer’s mark signaled a devotion to the Cross. John Siberch (1476–1554) was the first Cambridge printer and an associate of Erasmus. He had links with some of the key figures in North European printing and bookselling and, in turn, formed connections with leading theologians and scholars like Erasmus. Wikipedia notes that Siberch knew “the authors, translators and dedicatees who comprised many of the major contemporary figures of church, state and academia, including bishops John Fisher of Rochester and Nicholas West of Ely, Richard Pace, Secretary of State to Henry VIII, the royal physician Thomas Linacre and, above all, the great humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus and his circle, while the books touched upon significant issues of the day, such as religious reform and the new humanist learning.” [6] The St Alban’s Press was the third printing press established in England in 1479 as part of the Benedictine Monastery of St Albans, clearly a religious establishment that promoted the Cross as central to their printing. Erhart Oglin was a German printer focusing on printing music. In 1512 he was the first printer in Germany to produce “a printed sheet music, the Deutsche Liederbuch , which contains 43 German sacred and secular songs as well as six Latin songs.” [7] Juan Rosenbach was a Spanish printer whose printer’s mark can be seen in the Library of Congress today. The evident Cross stands over a sacred “h” perhaps referencing ancient Horus. [8] Bernardino Giolito de Ferrari, known as Stagnino, used at least three printers’ marks with variations — “The device employed most often is reproduced here from his edition of the Roman missal, printed April 7, 1511: the letter B is enclosed within a heart, surmounted by a cross; the staff of the cross pierces the letter S. While the letters B and S presumably identify the printer, an alternate device shows the figure of St. Bernardino of Siena (1380-1444), an Observant Franciscan friar, with similar initials. Stagnino's mark represented the saint with the IS monogram and three cast-off miters, symbolizing the three bishoprics he rejected in order to continue preaching his popular sermons against Catholic heresy and immorality.” [9] Indeed, a profoundly religious use of the mark. The mark of Hercules Nani, with the Cross, above three hills or mountains, may imply meditation and heavenly communion — “The Mountains of Myrrh and the Hills of Frankincense, to which the writer of the Song of Solomon says he will retreat, are ideally the same as those ‘silver mountains’ over which, according to Sir Walter Raleigh, ‘My soul, like quiet palmer/ Travelleth towards the land of heaven.’ Among the Jews the three-peaked Mount Olivet was esteemed to be holy, and accounted to be the residence of the Deity.” [10] The point here is that this printer’s mark indicates much more than a mere cultural convenience or capitulation to the period. Modern uses of printers’ marks continue, with the examples below of the Banner of Truth Trust, Penguin Publishing House and New North Press. The Banner printer’s mark has a deeply religious meaning and message. Often these marks are on the copyright or title page of the book today. They may also adorn the cover of such books. CARE Typography has meticulously digitized these marks and made them available as a typeface for your use. They are public domain images, free to use with the attribution — Digitized by CARE Typography, 2024. Notes [1] Maggie Patton, “The Printer’s Mark: That Curious Penguin on the Spine of Your Favorite Paperback Isn’t There Just for Decoration,” Openbook , Autumn 2022. [2] William Roberts, The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Printers’ Marks , June 1, 2008, Ebook #25663, from inages made available by The Internet Archive. [3] Roberts, pp. 24–26 [4] Ibid. [5] “the persistence of the cross;” “originated from affiliation with a religious brotherhood” quoted by Roberts, 24. [6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Siberch [7] https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erhart_Öglin [8] Harold Bayley, The Lost Language of Symbolism: An Inquiry Into the Origin of Certain Letters. Words, Names, Fairy Tales, Folklore, Etc. , 1912, p. 161, from Internet Archive Books. [9] Library Quarterly Information, Community, Policy , Vol. 83, No 1, pp. 39–41, The University of Chicago, 2023. [10] Bayley, Lost Language of Symbolism , 35.

By Carl Shank

•

19 Jan, 2024

Install Tricks for Double Drives on a Mac Mini. This Blog references upgrading Mac Mini 2011 to Late 2012 with double drives. If you want a video installation of the drives go to OWC at https://eshop.macsales.com/installvideos/mac_mini2012_server_hd/Macmini6-1-nonserver/ OR iFixit at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2NORZR0BbZs . Both installation videos are complete and helpful for the first-timer. But as a Mac Mini user (I have 4 of them with different operating systems), I have found the following procedure helpful and non-detrimental to the delicate ribbon cables inside the Mini. (I have learned through harsh experience how to inadvertently snap off the delicate fan or IR holder on the mother board. And buying an older machine, say on Ebay, can get you a machine with inside fragile parts that tend to snap off when using the video based installation procedures.) So, here you go. Turn the Mini over and carefully remove the back cover by sliding the white dot on the cover to the white dot on the machine. Remove the memory chips. Using a Torx T6 screwdriver remove the fan screws. DO NOT REMOVE THE FAN CONNECTOR FROM THE MOTHER BOARD! Just move it to one side. Remove the cowling using the T6 screwdriver. Using a Torx T8 screwdriver remove the hex screws holding the airport metal screen over the drive. DO NOT remove the cable attaching the airport cable to the machine. Set that to one side. Lift the SATA connectors on the logic board straight up gently. You should then be able to carefully lift out the hard drive from the Mini. If it seems too tight, then you need to move the logic board back only slightly by taking the screw out from the back of the logic board and then using a Mini pry tool move the logic board back just a bit from where the drives are. (Go to the videos here for this procedure. If you use this procedure then before the next steps you will need to push the logic board back in place after the drives are seated and put the back screw into the logic board.) Attach the lower drive SATA cable (SEE NOTES below) to the drive that will be the lower drive and gently push it into the generous space, being careful not to impact the fan cable or IR cable or power cable on the logic board. This can be done with a gentle hand and no need to fully remove the logic board and other components as in the video instructions. Attach the SATA cable to the upper drive you are using and gently place that drive into the upper drive slot. Attach the SATA cables to the two places on the logic board. Attach the airport metal screen being careful not to inadvertently unattach the SATA cables from the logic board. Attach the cowling. Screw the Fan back into its place. Place the memory back into the Mini. Put the back cover on by aligning the white dots and twisting the cover until it snaps into place. Unless you are constantly moving the Mini, this procedure will save you from either ruining the fan cable or logic board fan cable holder. You will not have to essentially take the Mini apart, put it back together, and hope that all goes well. I have used this procedure many times and have found it to be an acceptable alternative to the traditional video procedures. If you have any questions please email me at cshanktype@gmail.com. NOTES: • If using a Mac OS 10.8.x see https://eshop.macsales.com/blog/15619-special-note-for-adding-an-ssd-to-a-2012-mac-mini/#comment-61641 for necessary cautions. • SSDs are recommended to replace older hard drives. OWC has a number of options here at macsales.com. • You still need a Data Double kit for the SATA cables required.

By Carl Shank

•

16 Jan, 2024

A Bible Typography Manifesto . The Manifesto Below was crafted by Mark Ward (See BLOG Post "Good Bible Typography" Nov 10, 2021). It says what I have been thinking about as both a theologian and typographer. I will then offer some of my own comments — "BIBLE TYPOGRAPHY MANIFESTO https://byfaithweunderstand.com/bible-typography-manifesto/ WHEREAS typography is a major but often overlooked source of meaning, for good or ill, in any book, and Bible typography, in particular, has long been shackled by unexamined custom and consumer forces rather than shaped by readers’ best interests, and chapter and (especially) verse divisions have a comparatively brief history among God’s people, and prooftexting and other forms of hermeneutical atomism—which are abetted by a versified rather than a paragraphed Bible—are still rife among Christians, and computers have made good typography easily achievable, and computers have put extensive Bible study materials literally in the pocket of countless believers, WE, THE UNDERSIGNED, DO HEREBY CALL UPON ALL BIBLE PUBLISHERS THROUGHOUT THE WORLD TO limit the number of Bible editions published in two-column formats, and begin publishing most Bibles in paragraphed, one-column formats. These two items form the heart of our polite demands—but here are a few more for good measure, specifically directed at American Bible publishers: Publishers and readers alike must add a fundamental binary category to their thinking about Bible publishing: study editions and readers’ editions. Americans have enough money to have both kinds (and they also typically have access to computer resources for Bible study), so Bibles should cease trying to compromise between these two major categories of Bible usage. Study Editions should have superscript numerals and letters referring readers to other parts of Scripture and to explanatory material. They should still be set in a single column, but should include as much useful information for the Bible student as possible. But Readers’ Editions should be free of these intrusions. Readers Editions should, in fact, have nothing but the text, set in paragraphed formatting common to other serious non-fiction. Verse numbers, ideally, would be omitted in these editions. They might possibly go in the margin as an acceptable compromise, and a verse range can certainly be put in the header for each page, but anyone who needs to look up a particular verse can use a study edition or a computer/smart phone. (The Books of the Bible project is a good example of a Reader’s Edition. Update, 2014: Partly as a result of this manifesto , Crossway now offers an ESV Reader’s Edition .) Within the two categories above, feel free to produce as much useful variation as possible: wide margins, journaling editions, preachers’ Bibles, etc. Pay attention to typography. Pay actual designers to lay out your Bibles. There are standards for ideal line length, type size, and leading that have been established over the centuries. Lexicon is a exceptionally good typeface for Bible publishing. Do not try to sell Bibles by including cutesy material that undermines the gravity of the text—or edgy , worldly material that undermines its holiness. Bibles should not look like teen magazines or gift-store kitsch . The medium is part of the message. We are aware that evangelical Christians will be suspicious of any changes to The Way Things Have Always Been. But it’s time to learn a lesson from Steve Jobs, who didn’t know he was speaking about Bible typography when he said , “It’s really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” Jobs has proved that beauty of form actually enhances usefulness of function. The particular function Readers’ Bibles will serve is keeping the flow of thought going for Bible readers. The paragraphs will break up the thought where the thought itself breaks instead of at fixed intervals (as in our current system), and the single-column format—along with appropriate modern typographic conventions—will say “narrative” or “letter” (etc.) rather than “reference book,” as double-columns do. Treating the Bible like a reference book to the exclusion of Story has been one of the cardinal errors of evangelical interpretation. As John Frame points out ( DKG , p. 197), not all prooftexting is wrong; but plenty is. And double-column, non-paragraphed Bible text invites it, because it causes readers to think of “verse” as the fundamental unit of scriptural statement. Witness the evangelical predilection to include logical connectors when quoting a verse, despite the fact that they are unnecessary and confusing when quoted alone : “But God commendeth His love toward us… ( Rom 5:8 ).” Unversified text would invite readers to think of familiar verses as parts of paragraphs and overall discourses. We, the undersigned, commend some publishers, especially Crossway Bibles and Cambridge Bibles, for their sense of creativity and beauty in Bible typography. These have also led the way (along with companies like R. L. Allan ) in innovative use of new and old materials for beautiful, flexible, and lasting Bible covers—and in printing methods which allow, for example, rich color on thin Bible paper. THE UNDERSIGNED MARK LEE WARD, JR., B.A. Bible/Art, M.A. Bible, Ph.D. New Testament DUSTIN BATTLES, B.A., M.A., M.Div. ANDREW DAVID NASELLI , B.A., M.A., Ph.D. 2 BRIAN CURTIS COLLINS , B.A., M.A., M.Div., Ph.D. Theology Comment on this page to become one of the undersigned. Update (03/07/2012): The manifesto review committee now believes one line in the initial language to be unjustifiably intemperate (even though the whole format is tongue-in-cheek): “Immediately cease publishing Bibles in two-column formats.” Two-column formats do allow for smaller Bibles to be printed, and there may be other specialized reasons for having them. However, it is still the opinion of the committee that their predominance is unfortunate and unnecessary. Update (10/25/2013): The manifesto has been heard ! Update (7/24/2014): A groundswell is building ." My comments . There are several areas of concern I have always had in Bible typography and understanding. The first is the verse-by-verse atomistic reading, preaching, commenting and study that follow verse divisions and separates single ideas without giving full credence to context. Too many sermons, articles, books and study guides have been written and given without adequate consideration of the whole Bible context of a verse or thought. The Bible is the history of God's redemption of his people, and it is supposed to flow and develop and be read as a developing story until the end of the Book in Revelation. That is unfortunately rarely done, even with seminary trained and schooled church people. The second note is the lack of due typographic standards in the setting and printing of the biblical text. Proper typographical line length, type size, leading, and typefaces that have been established over the centuries of good typography are ignored and shuttled to the side for what is supposedly dramatic and consumer driven. Clean lines and readable, legible and clear text are sometimes missing in printed Bibles. This does not have to be so, given the wealth of good typographers and typographic standards we have available. Use them. Obey them. The third note is to get away from the cutsy, market driven Bible printing and distribution craze that has infected our churches and ministries — "that undermines the gravity of the text—or edgy , worldly material that undermines its holiness. Bibles should not look like teen magazines or gift-store kitsch . The medium is part of the message." This says it well. Children's and youth Bibles and teen editions and cute women's Bibles and supposedly tough "men's" versions litter the marketplace. Stop! This is God's Word that we are talking about, not some dime-store novel to play with and adapt at a whim. The argument for "relevancy" grows quite thin here. I am a signatory to this Manifesto. Will you join me?

By Carl Shank

•

10 Jan, 2024

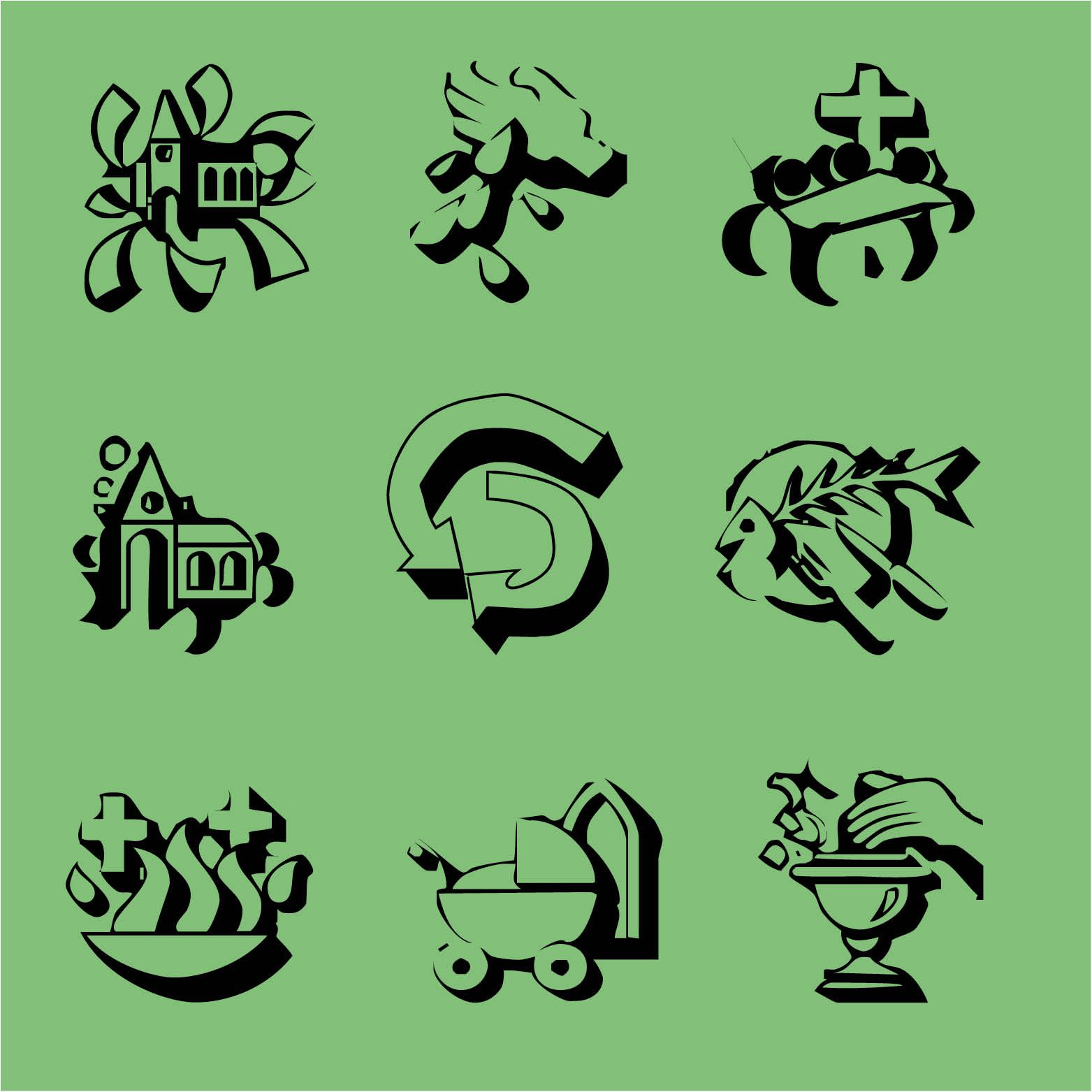

A New Ministry/Church Font . CARE Typography is pleased to release a new church/ministry font for use by non-profits and churches as well as ministry venues. This font is FREE to all such ministries. The Ministry Picts Font was adapted from Pictograms found in The Image Book: 2,500 Visual and Verbal Images To Clip and Use During the Church Year (C.I. Publishing, 1993). This image book was originally designed for image copying and use by church and ministry organizations. Developed thirty years ago for copying images for newsletter and other church uses, we found a number of Pictograms that can be updated and adapted for use by religious organizations. While no doubt dated, these Pictograms can add spice to your newsletters and church articles. Think of them as "retro" images. Some of the Pictograms offered in the Image Book are suitable for font development. We have used Fontographer 5 after cleaning up the images and making them suitable for typeface use. Since these Pictograms are now in font form, they can be sized and used most anywhere in church and ministry publications without concern for readability or clarity. CARE Typography recommends sizing at 100 points or higher for quality use. You can secure your copy of the font by emailing CARE Typography at cshanktype@gmail.com. Enjoy them!

By Carl Shank

•

15 Dec, 2023

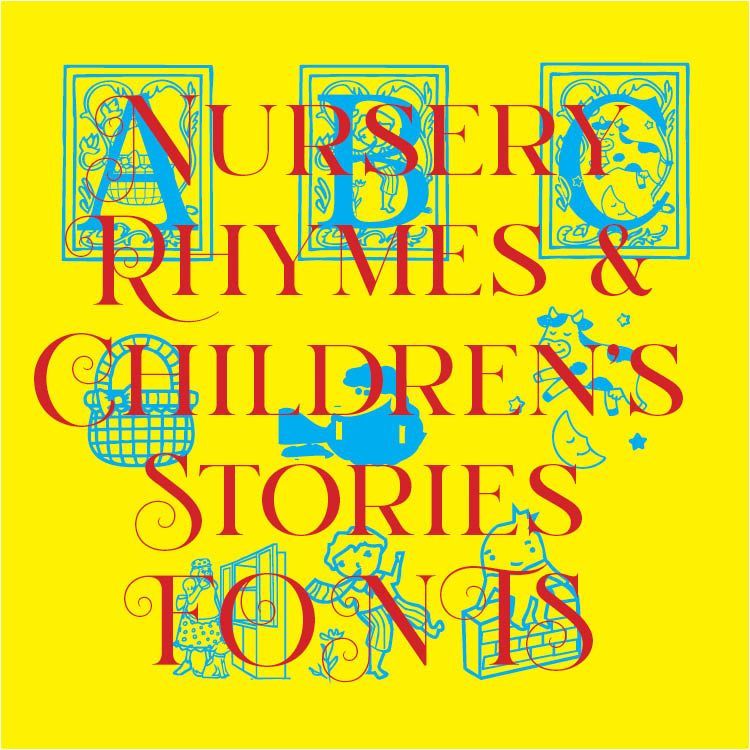

Introducing the StoryBook and Fairy Tale Fonts. I like reading old books with fanciful crafted title caps (called "versals" in the typographic world). They remind me of days gone by when a children's book, full of illustrations of well-know children's tales and Mother Goose stories, captured the attention of children and adults alike (See Illustration Below). What happened to those old, fun-loving illustrations and typefaces of long ago? Many would say they have outlived their time and usefulness. I disagree and have set about designing two new typefaces, called StoryBook and FairyTale, which seek to get us back to these fantastic old books and illustrations. Using a flowery old-fashioned border in the StoryBook Font, I have set capital letters against a backdrop of well-known nursery rhyme illustrations. These fanciful caps can be set as opening letters to a children's book or series of children's stories. I have attempted to find either public domain illustrations and then make outlines of the main characters using Adobe InDesign and Photoshop tools, or have purchased resources for fair use in such background designs. In the Fairy Tale Font, which has specialized characters, I have mostly utilized the fine work of others and adapted such work to scannable pieces from which I could create a suitable font. You will have to be the judge of the final product. I am very interested in your evaluations and comments. There are three iterations of the StoryBook font — StorybookSerif, StoryBookSansSerif, and StoryBookBackgrounds. The Serif font version uses letters adapted from the open source Libre Baskerville font. The SansSerif version uses Sans Serif open source font. The Backgrounds version has no inset font in the background diagrams. It also has a page where the font diagrams have been transformed into outline versions, thus allowing the user to employ the background in a variety of ways. One such variation is to use an outline font placed over the backgrounds to give the user more "storybook" like appeal. The StoryBook font is a collection of capitals along with some illustrations that can be utilized in a children's book. The Fairy Tale Font are illustrative pieces that can be used in texts or displays. I have also included in the Fairy Tale Font additional explanatory pages of the origins and use of the font. Samples of the fonts, used in well-known nursery and children's rhymes throughout the ages, are below. If you are interested in using the fonts, contact CARE Typography at cshanktype@gmail.com, for securing them.

By Carl Shank

•

06 Dec, 2023

Work or Craft? Is Typography and Printing “Work” or A “Craft”? I recently read an interesting and provocative chapter in the book by Dorothy Sayers, Letters to a Diminished Church: Passionate Arguments for the Relevance of Christian Doctrine . The chapter, “Why Work?” promotes work “not as a drudgery to be undergone for the purpose of making money, but as a way of life in which the nature of man should find its proper exercise and delight and so fulfill itself to the glory of God.” She goes on to say that “We should ask of an enterprise, not ‘will it pay?’ but ‘is it good?’; of a man, not ‘what does he make?’ but ‘what is his work worth?’; of goods, not ‘can we induce people to buy them?’ but ‘are they useful things well made?’; of employment, not ‘how much a week?’ but ‘will it exercise my faculties to the utmost?’” This got me thinking about typography and the printing profession. Are they “work” or, as Roger Bringhurst says, “Typography is the craft of human language with a durable visual form . . . its heartwood is calligraphy — the dance, on a tiny stage, of the living speaking hand — and its roots reach into living soil, though its branches may be hung each year with new machines. So long as the root lives, typography remains a source of true delight, true knowledge, true surprise.” ( The Elements of Typographic Style , 11) Such expressive descriptions of typography and the printing profession defies the historical and tedious work of typesetters and printers throughout the years. In the early years of printing, compositors and presswork became separated and almost at odds with each other. Compositors believed “their reading skills and proficiency in Latin and Greek made them superior to pressmen who presumably had been selected for their physical strength, a necessary requirement in the laborious operation of the hand presses.” (Alexander Lawson, “Thoughts on the Typo Workplace,” Electronic Publishing , 1994) He notes that “working conditions for compositors so employed approached the horrendous — long hours of work, from five in the morning to eight at night, lighting by candle and noisome lanterns, and the discomfort of 6-point type.” (Lawson) He quotes a letter written to the Typographic Journal in 1894 by the wife of a newspaper comp on the harsh conditions her husband had to labor — “I do believe that the morning newspaper, set by weary, sweating, half-blinded, nerve exhausted humans, who are driven to the saloon to recuperate by temporary exhilaration, and to early graves by soul and body enervating toil in unwholesome, ill-ventilated, stinking, over heated composing rooms is a greater curse to humanity than the much dreaded [Linotype] machine can ever be.” The mortality rate of TB among printers of the period was double that of the community as a whole, with alcoholism an acute problem. Of course, life itself was hard and harsh in those days with sweat shops and young children employed without adequate safety standards and unbelievably bad working conditions. Yet, Lawson says “we can be thankful to those old-timers who gradually, albeit painfully, brought about a workplace more amenable to health and prosperity.” Such “work” seems a long distance from the “craft” of typesetting and typography in general. Today, our problems are mostly orthopedic problems because of ill-designed seating or unhealthy computer-generated vision issues. This brings us to the central issue raised by Sayers — Do we work to live or live to work? Have we indeed forgotten that secular work is sacred work, and that quality of work, work worth doing and in which we can take pride has been replaced by consumerism and the unhealthy desire for more and more stuff? From the point of view of both a seminary trained professional minister and an amateur typographer, this is a crucial question for every printer and every typographer. There are relatively few professionally satisfied typographers and happy printers. I know a few. But I also know the drive to produce, produce, produce and to make more money all the time. The New York Times mantra, “All the news that is fit to print,” can be easily morphed into “All the news that will produce more money and more power.” Indeed, what is “fit to print” becomes “what will the market bear and want.” Mega-print houses can be driven to produce what will sell, instead of printing carefully crafted typographical pieces that will bring few monetary rewards. Do we live to print or print to live? Do I craft and set type to live or live to craft and set type? The problem is losing the craft of typography and printing to the pressure-driven business world of producing what will sell and make a profit. This is an age-old problem, of course, but I would ask my typography and printing friends for their answer — Do I do what I do to live, or do I live to do what I do? Sayers notes the fruits of living through World War 2 — “We have had to learn the bitter lesson that in all the world there are only two sources of real wealth: the fruit of the earth and the labor of men; and to estimate work not by the money it brings to the producer, but by the worth of the thing that is made.”

By Carl Shank

•

25 Nov, 2023

Want To Sell Your Book? Like some other POD (Print-On-Demand) or self-publishing projects, there are a number of considerations to take into account for selling your finely crafted or meticulously accomplished work. I have used a Kittl-based video* for this BLOG because it outlines so much of the basics for any self-published sale. There are, of course, other professionally written articles and online helps for publishing as well. I find the following points to be basic and helpful. Be careful of what is called the "race to the bottom." That is, pricing your work so low that you barely cover the costs, let alone make a profit on your work. One Kittl advisor notes that "You shouldn't deprive someone the opportunity to pay more for a product if they can." (Luna Vega) People are not merely looking for a bargain. They often are looking for something that they know is worth their money and investment. And they are willing to pay what not merely the market suggests, but also what it is worth to them. Having this business sense or savvy is important so that you do not undersell yourself or your book or product. Understand ALL the costs involved. Book and project publishing requires much more than what someone may suspect. Let me use my own publishing ventures as an example. I use Adobe InDesign, which is a wonderful layout and design tool, but it costs me, in round figures, about $58 per month for a subscription. And, you cannot use this product without a paid subscription, unlike the old days of software development where you could outright buy a program and use it without a monthly cost or fee. Microsoft also sells their MS Word, PowerPoint and other programs for a monthly fee. Again, gone are the days when you could just purchase Microsoft office, say, and be done with it. To use their products on modern computers and modern software programming, you will need to update older MS software to accommodate the new computer hardware or software. Unless you buy or use an older computer and ignore Microsoft's updates. Production and selling fees need to be considered . They include the charges a publisher, like Lulu in my case, will charge for their printing of a book or calendar or study guide. Consequently, they will "force" you to sell your book at their minimum pricing, which is usually far higher than the base publishing price they bill you. Added to this is your "time spent" cost for your project. You might not think this is a real cost, but all the time and effort and hours you have spent on a project should be considered in some tangible way. Then, there are always shipping fees and taxes that are charged by anyone you use to publish your work. So, in addition to my InDesign and Microsoft monthly subscription fees, I need to pay a yearly fee to host this website, which I use to advertise any project or book. And I need to pay for the domain fee and costs. Of course, many people, like myself, decide to "eat" such essentials and think they can still make money on their book or project. Market and advertising fees and costs need to be added to any project. I use PayPal for the collection of funds, but they charge a seller's fee for every sale I make. While a small percentage, it is enough to cut into any profit margin you may want. Etsy and Shopify and ECWID and other vendors charge a fee for selling your stuff. You need to count that into the final cost of your book or project. Research the market for your book or project . See what others are charging for a book of your chosen topic. You will need to find out what people are willing to pay for such a book or work. Consequently, I have designed some basic pictograph fonts I use regularly. However, similar fonts sell either cheaply or are given away online for just a notation of the author. This is due to the fact that the alphabet is not copyrightable, as are many images in the public domain. Unless you are a top-notch font designer working for a company like Adobe, you cannot make much money, if at all, for your font designs. Will people buy your "brand?" Do they know who you are and trust you enough to spend their money on your book or project? This is always the problem with start-up authors and lesser known people. You might get lucky and somehow tweak an interest on Facebook or another social media program and end up selling mega amounts of your book. That rarely happens. I have been invited to go on book tours and book signing events, but I would have to pay for these events upfront, with precious little sales at the end of the day. That would be a loss to me. SO, I have friends and acquaintances that buy my books or projects. Even with major and known names advertising your work, selling is still hard and uncertain. Understand what the market will bear. I sell PageMaker-to-InDesign conversion services. I have found that my base charge of $15 per file, though it may seem extreme to some, is what the current market will bear. I have converted old PageMaker files to newer InDesign files from across the world. No one has complained about the charge per file, knowing that I am one of a very few typographers that can actually do the conversion. I own all of the out of print previous PageMaker software in all its iterations and have the computer equipment on which to use this software. What will the market pay for what you are selling? What is your overall goal? I cannot make a living selling what I sell. I understand that and am willing to collect what many would call extra or discretionary income from what I publish and perform. I have always had a full-time job or profession and have written and published books and projects out of my brand as CARE Typography for the sheer enjoyment and challenge of such projects. I barely make enough to pay for all the subscription fees and cost of operation. That may seem like a losing proposition to many. But that is my choice. If you want to actually make money on your publications or projects, you need to do a whole lot of market research and invest enough upfront money to see a return down the road. Publish or sell for the sheer joy of the project and experience. This is what I have ended up doing. Whether or not something I have done "takes off," or no one buys what I have written or done, I have enjoyed the process. Maybe that is the real bottom line. (* See the POD Pricing Video on YouTube produced by Kittl at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrxahpuMr1I )