Good Bible Typography

Good Bible Typography. In a recent issue of Bible Study Magazine (November–December 2021), Mark Ward, editor, provided a well written and visual article "A Revolution in Bible Design: Meet the People Who Designed Your Bible." In that piece he reviewed the work of Bible designers and crafts people who design today's versions of the Bible, noting the typeface designs used and paper quality. In fact, in a YouTube segment, Mark has an entire talk on Bible typography well worth your time (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tu4t9FKn9M4).

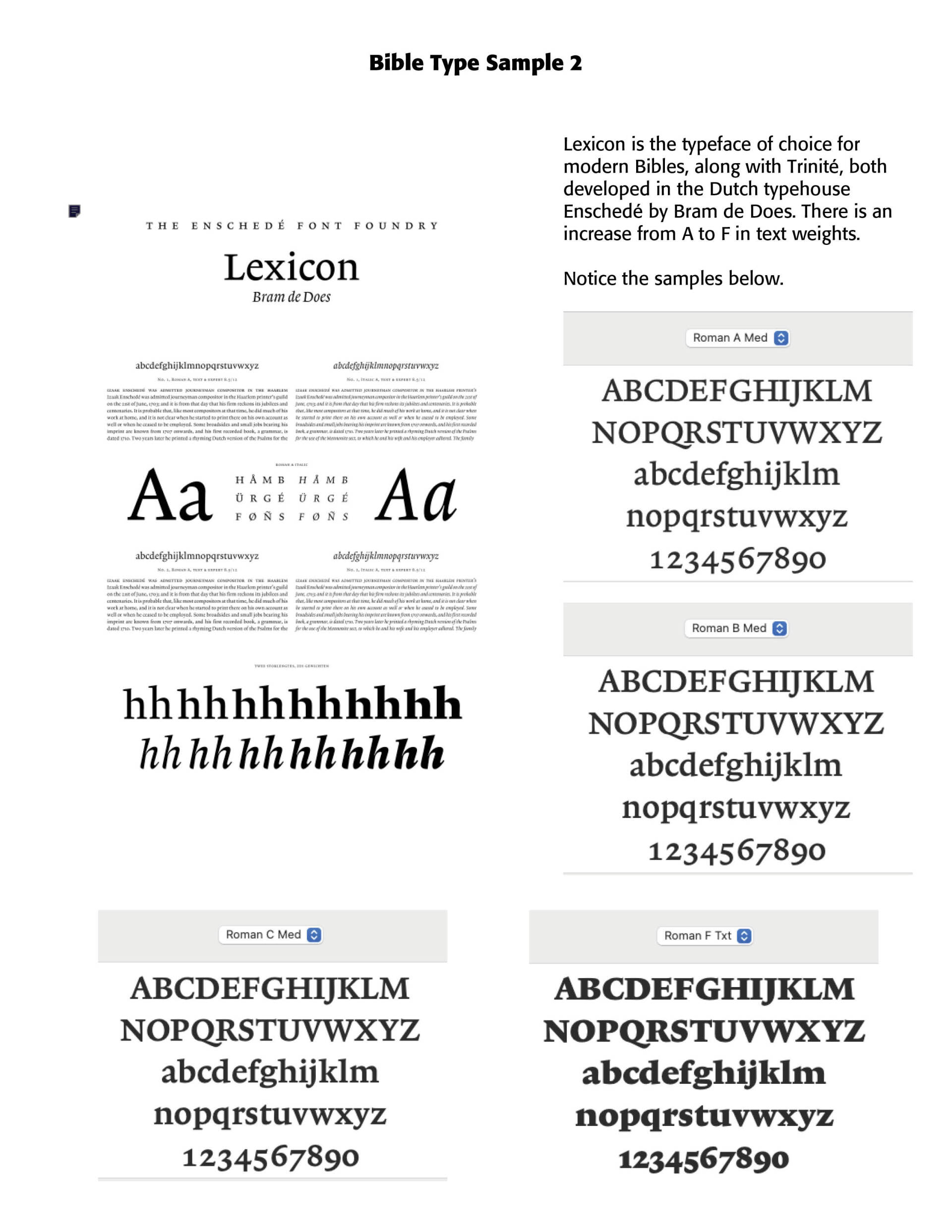

He quotes Dan Farrell, VP of Design Crossway (who publishes many modern Bibles, especially the ESV version today) on the best Bible font — "Bram de Does created two of the finest typefaces ever designed when he developed Trinité and Lexicon for Enschedé in the late 80s and early 90s. Lexicon is especially well suited to Bible design because of its option for shorter ascenders and descenders, its tall x-height, and its readability at small sizes. It has a calligraphic elegance without being delicate. For these reasons, I think it's a timeless typeface that will continue to be highly effective in Bible typesettings many decades from now." Indeed, a Google search for the type used in Bible today lists Lexicon as the most used Bible typeface with masterful Trinité N°2 Roman used in the ESV edition published by Crossway. (See Sample 1 Below)

There are a multitude of de Does Lexicon fonts available at various weights — two main groups: Lexicon No.1 and Lexicon No.2. Lexicon No.1 has short stems (ascenders and descenders); Lexicon No.2 has 'normal' stems. Both groups share the same widths thus making it possible to change fonts without reflowing text. Each main group contains 12 weight variants, six upright weights (A to F) and six italic weights (A to F), where A is the regular weight and F the boldest weight. These are expensive, asking over $4,000 for the complete set, and over $2,000 for set No. 1 or No. 2. (See Sample 2 Below).

Why is Bible typography important? The older KJV (King James Version) two-column Bibles often used by congregants were ill-designed, hard to read at small sizes, and each verse a separate paragraph with verse numbers and other markers interrupting the flow of the textual thought. They were not reader-friendly Bibles, and they often separated biblical thoughts and gave unfortunate fuel to "biblicism," that is, quoting verses and thoughts out of context. Atomistic quoting of single verses became the trend of preachers and well-intentioned Bible study leaders. Contexts were ignored, and through bad typography verses were clumped together in an unfortunate manner. Mark Ward offers some notable examples and instances of this in his YouTube talk.

Those who appreciate the biblical text want it read accurately and legibly. Paragraph divisions were incorporated into the Biblical Hebrew (Old Testament) and Greek texts (New Testament) arbitrarily. Even the verse numbers and divisions were arbitrary, supposedly for better study of the inspired Word, but led to unfortunate theological problems and even heretical points of view. The point I am making is that while we need to study the Bible as the Word of God to us and pore over the biblical theology therein, we need better Bible typography to do so.

Successful Layout & Design