Ancient Alphabets

Ancient Alphabets. How did our alphabet come to exist? Much of what we know about the alphabet comes from Middle Eastern and Egyptian sources. In my previous BLOG ("What's In A Name?") I investigated the creation of the alphabet and how our modern letters were formed. Again, I refer the interested reader and researcher to the excellent work by David Sacks, Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet from A to Z, available at Amazon.com. This particular blog offers readers and historical users the opportunity to see and download several ancient alphabetic fonts that history has uncovered.

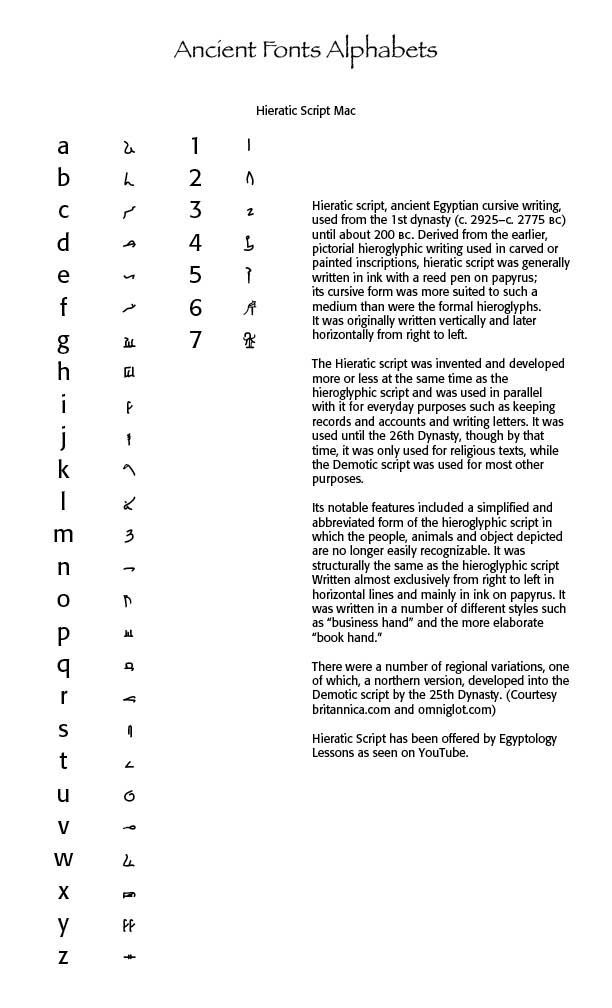

It should be noted that in the computer world, Google fonts has produced several ancient fonts, only in Unicode offerings. They are Noto Sans Cuneiform, Noto Sans Egyptian Hieroglyphs, Noto Sans Ugaritic, Noto Sans Old Persian and Noto Sans Imperial Aramaic. These are extensive fonts with hundreds or even thousands of characters in Unicode format. What that means is that finding a particular pictogram or etching (what ancient fonts look like) for a particular letter is next to impossible, unless one knows the exact letter font coding. They are also open source fonts, available for use and reconstitution.

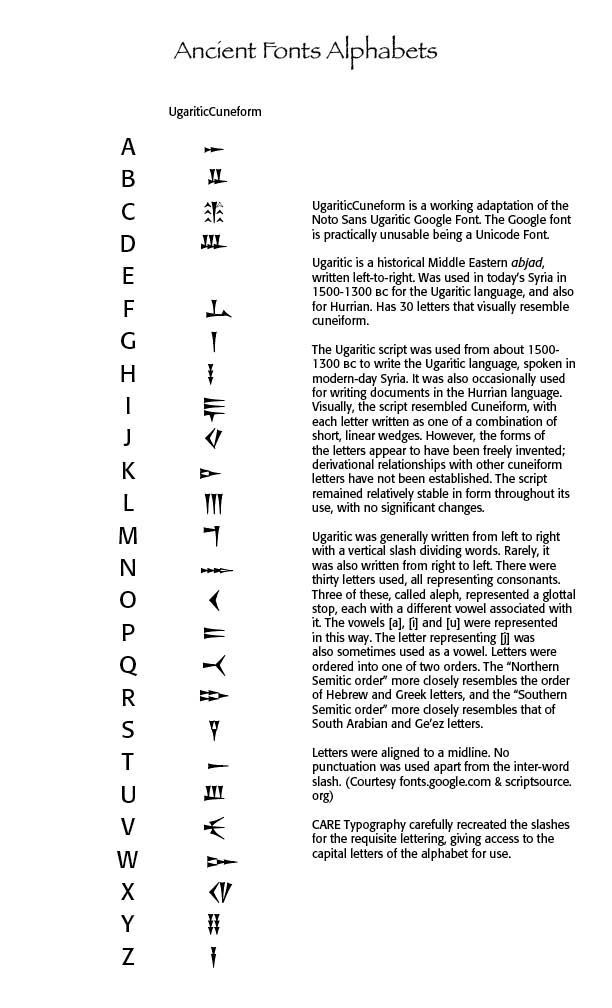

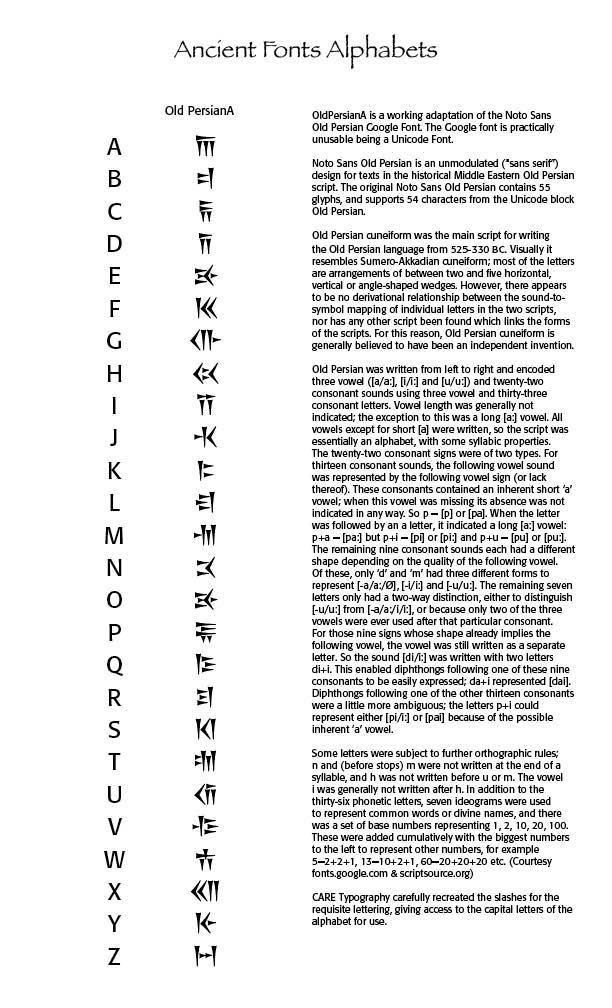

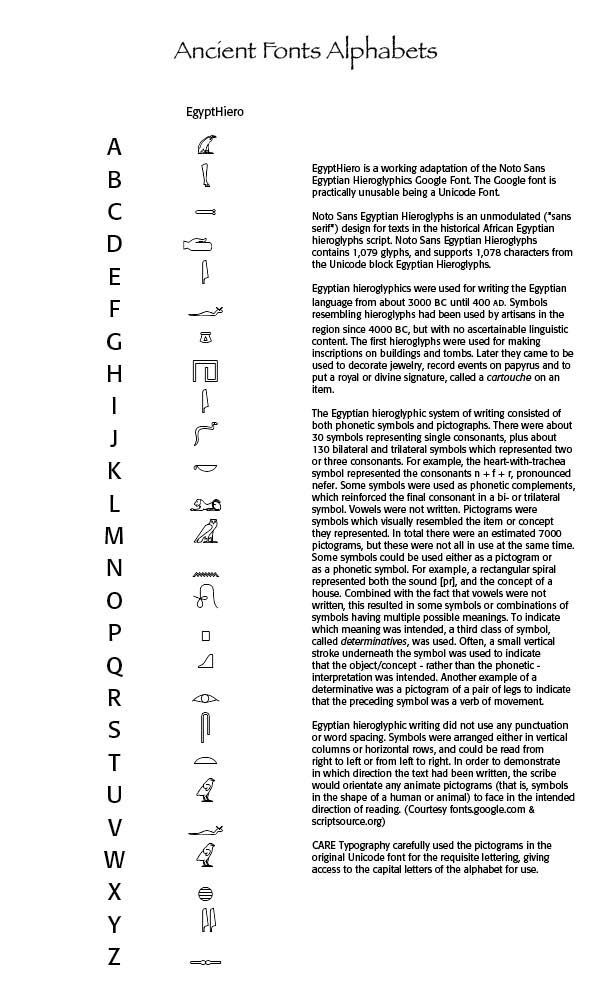

Using a reliable historical source, we can match letters or numbers to font glyphs. Consequently, what CARE Typography has been able to do is to recreate some of these ancient fonts that match the alphabet's capital lettering. Thus, in the Noto Sans font for Egyptian Hieroglyphs when you type the letter "A" you get back "A," not the Egyptian Hieroglyph for "A." The same holds true for the other Noto Sans fonts. We were able to reformulate some of the ancient fonts so that "A," for instance, gives you the correct ancient letter or pictogram. Note the diagrams below.

EgyptHiero. This is the reconstituted Noto Sans Egyptian Hieroglyph only for the capital letters of our alphabet. A bit of history here. Egyptian hieroglyphics were used for writing the Egyptian language from about 3000 BC until 400 AD. Symbols resembling hieroglyphs had been used by artisans in the region since 4000 BC, but with no ascertainable linguistic content. The first hieroglyphs were used for making inscriptions on buildings and tombs. Later they came to be used to decorate jewelry, record events on papyrus and to put a royal or divine signature, called a cartouche on an item. The Egyptian hieroglyphic system of writing consisted of both phonetic symbols and pictographs. There were about 30 symbols representing single consonants.

UgariticCuneform. This is the reconstituted Noto Sans Ugaritic font only for the capital letters of our alphabet. Ugaritic is a historical Middle Eastern abjad, written left-to-right. Was used in today’s Syria in 1500-1300 BC for the Ugaritic language, and also for Hurrian. Has 30 letters that visually resemble cuneiform. The Ugaritic script was used from about 1500-1300 BC to write the Ugaritic language, spoken in modern-day Syria. It was also occasionally used for writing documents in the Hurrian language. Visually, the script resembled Cuneiform, with each letter written as one of a combination of short, linear wedges.

OldPersianA. This is the reconstituted Noto Sans Old Persian font, again only for the capital letters of our alphabet. Old Persian cuneiform was the main script for writing the Old Persian language from 525-330 BC. Visually it resembles Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform; most of the letters are arrangements of between two and five horizontal, vertical or angle-shaped wedges. However, there appears to be no derivational relationship between the sound-to-symbol mapping of individual letters in the two scripts, nor has any other script been found which links the forms of the scripts. For this reason, Old Persian cuneiform is generally believed to have been an independent invention.

Successful Layout & Design